This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 6, now on sale at The Legendary Lead Company. I have just a few hard copies left of the first printing, available here, and an ebook version in pdf format is available for download here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

I already had an example of this pencil, but when one with box and instructions comes up, I can’t help but upgrade if the price is reasonable:

Unfortunately, the box wasn’t right – a cardboard base with an unrelated plastic top with tabs to snap into something else... just something to give a seller that extra bit of “NOS” flavor to sucker in a guy like me. At least the pencil is nice:

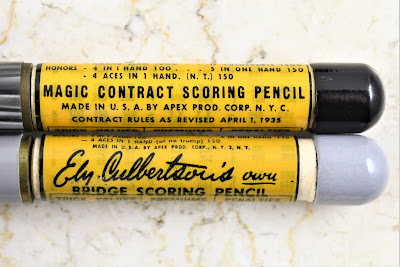

It’s an example of “Ely Culbertson’s Own Bridge Pencil” and it was made by the Apex Products Corporation of New York, makers of the Apex “Magic Multiplying Pencils”:

These had a built-in cheat sheet to help you calculate how much to bid in the card game of contract bridge. Turning the barrel revealed numbers on a scroll inside. The instruction sheet shows how:

The mechanics are the same as what Apex employed on its “Magic Multiplying Pencils” and, in fact, Apex also made contract bridge pencils in that form, too:

The striated example has a slightly different imprint: it is simply a “Magic Contract Scoring Pencil” and it reflects rules updated on April 1, 1935.

The boxed Ely Culbertson example has no date, so I don’t know whether the celebrity spokesman signed on before or after 1935. The “Contract Bridge Game of The Century” took place in 1931-1932 (yes, it kept going while the calendar flipped over to the new year) and Culbertson’s last tournament appearance was in 1937, so it could have been either.

And, Culbertson didn’t just lease out his name to Apex:

These operated on the same principle as the Apex - the center barrel section rotates around a printed scroll, revealing different bid calculations based on different scenarios. However, they weren’t made by Apex:

These “Culbertson Scoring Pencils” were made by Salz, and while the imprint indicates that patents were pending, I wasn’t able to find one that lines up with what I’m seeing here. Perhaps someone else beat Salz to it, or he was licensing the rights to make these pencils from someone else:

This one also has Ely Culbertson’s name on it – and a patent number:

Nicholas E. Nicolet, of New York City, filed a patent application for his scoring device on October 8, 1931, and his patent was issued on May 24, 1932 as number 1,859,524.

This patent doesn’t appear in

American Writing Instrument Patents Vol. 2: 1911-1945; although the patent shows his invention incorporated into a pencil or pen, it wasn’t filed under the categories in which pens and pencils were patented. This one was filed in category 235, for “Registers,” subcategory 87R, “cylindrical.” Nothing short of reviewing every patent would have turned this one up!

However, since I was now in that neighborhood, I checked this odd category to see if there were any other patents along these lines worth reporting to you today, and I found one – in fact, it may well be the one licensed to Apex for its “Magic Multiplying Pencils”:

Helen Rowe Thomas and Adolph A. Thomas acquire this design patent on an application filed October 24, 1928; it was issued on March 4, 1930 as Design Patent 80,646.

(Note: I’d also photographed and nearly included other bridge pencils, a “Vanco,” one made by Welsh Manufacturing Co., and an unidentified one. Then I searched “Vanco” because I knew I’d seen an advertisement for them somewhere, and the first thing that popped up was the article I wrote about them here in 2018. Rather than repeat myself, see

https://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2018/03/trick-pencils-for-tricks.html.)