This article has been included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 7, now available here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy the article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

One of the items that I received from Don Jacoby’s collection was this little gem - I knew what it was without reading the imprint:

I’ve only seen those floral bands at the top and bottom of the barrel, with another floral band running diagonally between them, in two other places . . .

. . . that is, on the two other examples I have of this same pencil:

These are all marked “Perfect Point”:

The top example is the one that caused me to explore the history behind this brand during the first year of the blog (Volume 1, page 334). The Perfect Point was the flagship product of the Stull-Boylson Company of Fremont, Ohio (he said, swelling as I did in Volume 1, with Buckeye pride).

Jacob Henry Stull, of Fremont, Ohio, applied for a patent for the Perfect Point on June 19, 1919, and it was granted December 7, 1920 as number 1,361,115:

The drawing shows why my other two examples aren’t working. The example from Volume 1 is missing the propelling rod, and the second one that limped into the museum is missing . . . well, pretty much everything inside:

I was thrilled to find that Don’s example is in working condition. What made the Perfect Point special was a truly elegant design: the pushrod and screw drive is just a single piece of wire, wrapped around the inner tube to engage threads inside the barrel:

The Perfect Point was offered in a wide range of varieties during its short but spectacular run. The short models are typically ringtops, with a distinctive bail over the top crown. Very rarely, short models with clips turn up:

Then there are the longer models, which cut a commanding presence equal to anything the best pencil manufacturers were offering at the time:

“The Pencil That’s Always Sharp,” the box lid at bottom states.

The green gold example with price tag indicates that the Perfect Point was a luxury item, with a $6.00 price tag that exceeded the cost of a Parker “big red” Duofold at the time:

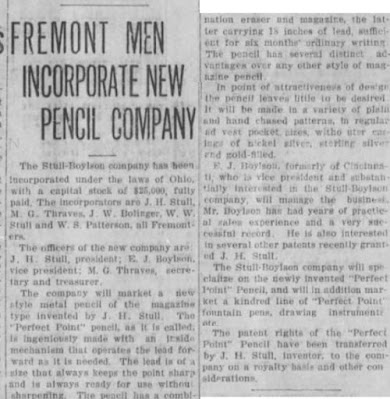

The fact that these were so well made, and so many have survived, led me to retrace my steps and see what happened to the Stull-Boylson Company to cut short the brand’s life. Formation of Stull-Boylson was announced in the Fremont News Messenger on June 23, 1919:

Several local men were the incorporators, but the three officers were Jacob Henry Stull, President; E.J. Boylson, “formerly of Cincinnati,” Vice President, who is described as having years of experience and who also “is interested in several other patents recently granted to J. H. Stull.” The new company’s secretary and treasurer was local attorney M.G. Thraves. The Perfect Point was Stull’s only writing instrument patent; his other patents related mostly to improvements in railroad cars and equipment.

Perfect Point pencils were available by mid-1920. The first mention I found was when they were made available locally by Druggist H.W. Birkmier, who advertised them in the News-Messenger on June 1, 1920:

By 1921, Stull-Boylson had engaged in a national advertising campaign to promote the new pencils. This advertisement is from the Oxford (Kansas) Register on September 8, 1921:

Stull-Boylson, as the initial account of its formation indicates, was only “marketing” the Perfect Point pencils. They were actually being made in Attleboro, Massachusetts - the heart of jewelry production in the United States. E.J. Boylson was Stull-Boylson’s Attleboro connection: that “formerly of Cincinnati” bit from the initial announcements of the company’s formation was added just for a little all-Ohio flair.

What isn’t clear is whether Boylson was affiliated with some other manufacturer which made Perfect Point pencils for Stull-Boylson, or whether Stull-Boylson had set up its own machinery and equipment in Attleboro to make the pencils itself. I haven’t found any evidence to confirm the latter, so I’m suspecting the former.

By late 1922, as demand for the Perfect Point pencils was taking off on a national scale, there was a shift in whatever this Attleboro-Fremont arrangement was, and Jacob Stull and E.J. Boylson began making plans to bring its manufacturing operations in-house and integrate them with the company’s executive offices. They chose Lima, Ohio, some 80 miles southwest of Fremont, as a suitable location.

On September 6, 1922, the Lima (Ohio) Gazette and Republican published an announcement that Stull-Boylson was considering locating there, “If Lima citizens subscribe $50,000 of the $200,000 capital stock.” In the article, A.E. Stull is named as the company’s president, replacing the inventor of the pencil, Jacob Henry Stull:

In order to further fan the flames of interest, Stull-Boylson begin advertising in the paper on September 15, 1922:

The stock offering – according to Stull-Boylson representatives – was an immediate, runaway success. Just a month later, on October 15, 1922, the Gazette and Republican announced that $50,000 in local investment had been secured, a site for a new factory had been purchased on Water Street, and the company was relocating to Lima. Plans must have been in motion well in advance of the September stock offering, since the article provides specific details concerning the planned factory, which would measure 50 by 200 feet with three sides made of glass. “[T]he first story of the building will be completed and the plant [will be] in operation by mid-December,” the report indicates . . .

. . . MAYBE. There’s a few curious details in this news story that suggest something more was afoot. First, the report states that the “Perfect Point Pencil company” (that’s “company” with a lowercase “c”) was relocating to Lima – maybe that was shorthand, since people in Lima might not have associated Stull-Boylson with the pencil’s brandname, but it might also indicate that a new company separate and distinct from Stull-Boylson was being set up for a fresh, new venture . . . rankling local investors who had so recently been enticed to invest in Stull-Boylson.

Second is the activities of E.J. Boylson detailed in the report. He was in town to consult with the architects about the new factory when the account was published, but at the end of the article, the story states that “Boylson will leave Lima this morning for the east where he will purchase machinery which will give the local plant five times the capacity of the Attleboro plant, it is said.”

What followed was an almost immediate implosion of the company. On December 12, 1922, notice was published in the Gazette and Republican that Stull-Boylson had applied to amend its Ohio securities license so that it could deal in its own securities, rather than going through A.A. Meggett, the company’s agent of record:

Then, just six months later, McAllister’s Book Store in Fremont, Ohio published a large advertisement in the News-Messenger announcing that it had purchased “the stock of the Stull-Boylson Mfg. Co., who are retiring from the manufacturing business.”

The collapse of Stull-Boylson now takes on the characteristics of a century-old murder mystery. Who killed the company, just as its coffers were full of fresh capital and the fortunes of its flagship product were on a meteoric rise? All of the scenarios are fascinating.

1. Perhaps the company made a huge gamble and overextended itself - if the $50,000 capital drive didn’t really succeed, contrary to Stull-Boylson’s statements, that might explain why Stull-Boylson wanted to fire its stock agent.

2. If Stull-Boylson was having an unknown Attleboro firm make its pencils, that manufacturer might have refused to sell the company the equipment it needed to put itself out of business – or even used its connections to prevent those from whom it acquired those machines from selling to him.

3. Jacob Stull’s replacement as president suggests there may have been internal struggles that brought down the company.

4. Maybe the stock offering to local investors invited a Trojan Horse takeover. A century ago, Lima, Ohio was primarily an agricultural center. Where would $2 million (in today’s dollars) in local investment have come from? While the report indicated stock was offered only to local investors, it would be easy for someone else – someone with a motive to kill off the company – to quietly finance the acquisition of a controlling interest in Stull-Boylson and use that position to quietly and legally put an end to it.

I have two likely suspects. The less likely of the two would be whatever shadowy Attleboro firm was making the Perfect Point before the company decided to do its own thing rather than have someone else do it for them.

The reason I believe that is less likely is that there would be no financial incentive: sure, they might have quoted a buttload of money for the machinery, and they might have obstructed the company’s efforts to leave. However, after the decision was finally made to terminate whatever relationship ended, the only motive remaining would have been revenge, sort of a “if we can’t have you, nobody can have you.” No businessman – particularly any businessman answering to their own investors – would commit that sum of money just to quelch an outgoing customer like a spurned lover.

A more likely culprit, if this is what happened, would be Wahl Eversharp. I previously noted how that Perfect Point box lid, with its “Always Sharp” tagline, might have been playing things close to the line in going head-to-head with the pencil giant. However, the company was actually well over the line, just by adopting the name “Perfect Point,” even if it was in quotes on the pencil’s imprints. Shortly after Wahl entered into the pen and pencil business, stationer advertisements across the country touted the Eversharp in company-supplied language: as “The Perfect Point Eversharp”:

Wahl would have had a legitimate business reason to squelch an up-and-coming new pencil company, which was capitalizing on a name Wahl used extensively in advertising, but never registered as a trademark. How much would Wahl invest to gain control and then quietly kill a rival?

We know Wahl spent the equivalent of $1 million in today’s money to purchase the Boston Fountain Pen Company. Throwing another million or so to gain control of something that might be a real threat to their investment? That might not have been seen as throwing good money after bad.

As I investigated all these possibilities, though, a much more likely scenario took shape – the possibility that Stull-Boylson and the Perfect Point were simply collateral damage in a much bigger game. The first step in establishing the perfect storm that ended the Perfect Point is to have a closer look at the Perfect Point’s nearest relative: the Acme.

1 comment:

Very interesting article. Thank you for creating it. I have this pen and was wondering it's worth and if anyone was interested in it since it is beautiful but of no use to myself.

Post a Comment