This article has been included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 7, now available here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy the article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

Note: if you're just joining the story now, you might check out yesterday's installment first, at https://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2021/07/correcting-more-than-typo.html

From yesterday’s article, we know there were potentially four outfits offering pens marked Eclipse through 1911: (1) whoever was having Laughlin make Eclipse-marked pens (maybe “L.A. Wright,” although the only evidence of that is from 1891); (2) Laughlin itself, which briefly adopted the name as a brand; (3) whoever was “specially making” Victorian-style dip pens for Hartwell’s; and (4) the “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company” which surfaced in Hartford, Connecticut just as the building in which it maintained offices was about to be demolished.

I never found evidence of the fifth alleged incarnation, in which Marx Finstone set up an Eclipse Pen Company in San Francisco in 1903. That’s one version of the story that has come down to us, and unless concrete evidence surfaces to support this story, I conclude this version is just a myth.

The other version, from “The Rise of Eclipse” by John Roede, published in the July, 2006 issue of Pen World (Volume 19, No. 6, page 28), provides that Marx Finstone emigrated to the United States from Poland in 1906 at the age of 31. Over the years, Roede’s version has been garbled a bit as it has been retold to state that Finstone founded Eclipse in 1910, when Roede wrote nothing of the sort: he stated only that Finstone had become established in New York in 1910 and “renamed the company Eclipse” sometime between 1913 and 1918, moving to 42 Houston Street, New York around 1918.

Roede’s version, if true, is the last nail in the coffin for the 1903 San Francisco version, and his version is much closer to the truth – closer, but not quite right.

Richard Keith pointed out the earliest reference to Finstone’s involvement in the pen industry, which appears in a Court opinion filed in 1925 (Parker Pen Co. v. Finstone, 7 F.2d 753 (D.C.)). In that case, the Parker Pen Company unsuccessfully attempted to restrain Finstone from making red pens with black tips. The Court ruled against Parker, and in the opinion Judge Winslow made the offhand remark that “Defendant has sold pens since 1907.”

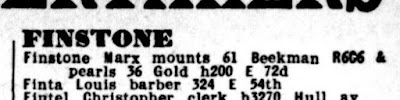

Unfortunately, Judge Winslow doesn’t say whether Finstone was making the pens he was selling or where he was doing so, whether in Poland, or New York, or somewhere else. Finstone does not appear in New York City Directories until 1910. His business is listed simply as “pens,” at 61 Beekman, Room 606:

Could Finstone have been in Hartford, Connecticut between 1906 and 1910? Possibly. Could he have attempted to source pens from Laughlin as the “Eclipse Pen Company”? Very unlikely – as indicated in yesterday’s article, Laughlin was apparently sourcing pens from New Jersey (why would Finstone not source them locally?), and the “Eclipse Pen Company” that stood up Laughlin had failed by September, 1906.

Could he have been behind that “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company” that surfaced briefly in Hartford in 1911? I don’t think so – sure, he might have maintained offices in Hartford after establishing his New York office in 1910, but the evidence overwhelmingly suggests otherwise: (1) although Finstone is listed in “pens” in the 1910 New York directory, no “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company” is listed; (2) the trademark registration for “Eclipse” says the name had been use by applicant and its predecessors since 1919 rather than 1911, and (3) after 1911, there is no reference to an Eclipse Fountain Pen Company in newspapers until this advertisement ran in the Bridgewater, New Jersey Courier-News on December 22, 1920:

City directories reveal that Finstone may have had multiple business interests. The 1911 directory shows him still in Room 606 at 61 Beekman, in “mounts” – that could mean metal overlays for pens, or settings for precious stones in rings and other jewelry. He has a second business address, at 36 Gold, in the business of pearls:

On April 2, 1912, The New York Tribune reported that Marx Finstone (and not Eclipse) had rented space in the new Turnbull Building, 161 Grand Street, New York:

The 1913-1914 City Directory is puzzling. Marx Finstone is listed at 161 Grand in pens, just as one would expect; however, there is also a “Mark Finstone” in the business of “mountings” at 51 Maiden Lane. There are different residence addresses listed for them:

For 1915, Mark Finstone disappears; Marx Finstone is at 161 Grand;

The 1916 directory appears at first to confuse matters even further. “Mark Finston” is listed in pens at 161 Grand; another Mark Finston is listed, affiliated with Pitzele, Hamburger and Finston. “Max Finstone” is identified as president of the New York Septic Hard Rubber Syringe Company:

The Mark Finston at 161 Grand is clearly our man, and so is “Max Finstone.” The India Rubber World published the Polyglot Rubber Trade Directory in 1916, and on page 338, the directory reports the incorporation of the “Nu Septic Hard Rubber Syringe Co., Inc.” on September 22, 1916. Our Marx Finstone was listed as one of the incorporators; another was a Henry Klein – maybe the name is coincidental, but David Klein would later assume a prominent role in Eclipse:

The 1916 directory clears up the confusion in the 1913-1914 directory, which lists two “Mark Finstons” with different residence addresses. There were in fact two men, and by coincidence both were in “kindred trades.” On May 2, 1917, The Jewelers Circular reported that Mark Finston had withdrawn from Pitzele, Hamburger & Finston and “has gone to Oklahoma, where he is now engaged in the oil industry.”

Our Marx Finstone clearly did not leave New York to pursue a new career in the oil industry; he is listed in the 1917 and 1918 directories, still at 161 Grand, and still as “Mark Finston,” but the listing for the syringe company has been dropped. In the 1920 directory, he is listed as “Marx Finstone,” this time as “Manufacturer of Fountain Pens,” still at 161 Grand:

No “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company” is listed in the New York directories between 1910 and 1920; while Finstone might have adopted the brand name “Eclipse” during this time, he was acting as a sole proprietor. In 1917, he advertised in the 1917-18 edition of Fogerty’s Directory of the Jewelry and Kindred Trades, but there’s no mention of Eclipse:

Since the Eclipse Never Dull pencil was a twist action pencil, rather than a “clutch pencil,” Finstone was likely sourcing Heath-style pencils to match fountain pens like these, although I’ve never seen one marked “Finstone,” “Eclipse” or any other brand associated with Marx Finstone – dear reader, that is your cue to say “challenge . . . accepted.”

There are Eclipse-marked pens which have a patent date of August 28, 1917; that is a reference to patent number 1,238,657, the earliest of several patents issued to Marx Finstone:

That does not mean Eclipse-marked pens were made beginning in 1917; it only means they could not have been made earlier than late 1917. Only an Eclipse-marked pen with “Patent applied for” marked on the lever would establish that Finestone adopted the name earlier than 1919, as the trademark certificate indicates.

On December 4, 1921, The New York Tribune reported that Marx Finstone had purchased the building at 42 Houston; although the “Eclipse Fountain Pen Co.” first appeared in newspapers in 1920, it appears Finstone had not yet formally incorporated:

The “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company” first appears in the New York directory for 1922-1923, at 42 Houston and associated with “Max Finstone.” The listing for Marx Finstone identifies him only as “Fountain Pen Manufacturer,” rather as president, further supporting the suggestion that he had not yet formally incorporated the company:

On January 7, 1922, the Federal Trade Commission prosecuted Marx Finstone individually for printing “fictitious and exaggerated” prices on his products; again, there is no mention of “Eclipse Fountain Pen Company”:

Even though he faced personal liability in the proceedings, Finstone apparently didn’t see the need to formally incorporate. Even in the 1925 directory, there’s no change in the listings to suggest that a corporation had been established.

Richard Keith tracked down notice of the formal incorporation of The Eclipse Fountain Pen & Pencil Corporation, “an established business,” in Office Appliances in December, 1925.

Just in the nick of time – the Federal Trade Commission came after Finstone a second time in 1926 for essentially the same allegations the Commission had made in 1922. Incorporation didn’t fully shield the individual actors; while the FTC named “The Eclipse Fountain Pen and Pencil Corporation” as a Defendant, the complaint also included Marx Finstone, his wife Lillian, and David Klein (inventor of the 1923 patent clip, among other things). This time, however, the case was dismissed after a hearing.

Things were starting to turn up for Marx Finstone: as mentioned earlier, Parker’s lawsuit against him had failed in 1925, and he had been vindicated in front of the Federal Trade Commission in 1926. Then, just as it looked like smooth sailing was ahead for Eclipse, Marx Finstone died unexpectedly on December 22, 1927 . . .

and then the fight really started . . .

1 comment:

Hi. I read your article about Marx Finstone now. I have a fountainpen marked: Marxstone on the pump and the clips is marked Safety. The pen tip is marked Eclipse, 14KT. The top of the pen is also marked 1/30-14KT.

Can you help me and explain if Marx Finstone has anything with this pen to do? I cant find anything at all on the internet.

Thanks in advance.

Post a Comment