This article has been included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 7, now available here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy the article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

In “To Out-Heath Heath” on July 19 (https://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2021/07/to-out-heath-heath.html), I wrote about Charles Keeran’s decision to change suppliers for his Ever Sharp pencils in October 1915, from the George W. Heath Co. to the Wahl Adding Machine Company. Keeran claimed the move was to increase production - he had no qualms about the quality of Heath’s work, but Heath wasn’t able to keep up with the demand for Ever Sharp pencils.

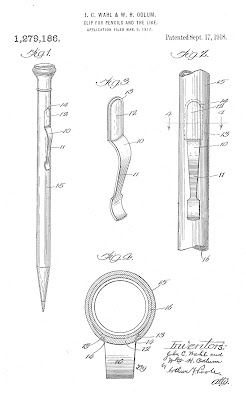

The transition appeared to be a clean break, with no overlapping production. Heath did not license Wahl to use Heath’s patented clips, so the earliest Wahl-made Ever Sharp pencils sport Keeran’s hastily improvised “spade clip,” for which Keeran applied for a design patent he applied for a patent on April 4, 1916. After Keeran’s clip proved too labor-intensive in production, John Wahl applied for the familiar tombstone-shaped clip found on millions of Eversharps on March 8, 1917 (note: Wahl contracted “Ever Sharp” to “Eversharp” in 1918).

As mentioned in my July 19 article, Wahl also had to cook up engine-turned patterns for the barrels on these pencils from scratch. “Apparently, Heath wouldn’t share tooling or otherwise allow Wahl to make the same patterns for Keeran’s Eversharps, either – the patterns found on Heath-clip Eversharps are generally not found on pencils made by Wahl,” I wrote.

I narrowly avoided being wrong. Scratch that . . . maybe I should say I narrowly avoided drilling a round hole, into which today’s square peg doesn’t fit. I thought, but did not say, that Wahl made everything in-house from day one and did not source any parts from Heath.

After that last article ran, Douglas Heinmiller, who contributed several images to A Century of Autopoint, emailed me some pictures of an Ever Sharp that fits within the article I wrote, but not within what I was thinking when I wrote it:

This example sports one of John Wahl’s patented tombstone clips – which I should think means it was made after Keeran made the move to Wahl in October 1915, and even after Wahl abandoned Keeran’s spade clip. There’s one H of a problem, though. Two “H’s,” actually . . .

Both the cap and the barrel are stamped with George W. Heath’s hallmark. Heath’s mark is included in American Writing Instrument Trademarks 1870-1953 – not as a Federally registered mark, but in the appendix, illustrated in the 1904, 1915, and 1922 editions of Trademarks of the Jewelry and Kindred Trades:

Douglas’ pencil is fascinating, because it does not square at all with the completely consistent story we thought we knew. It is the first example of an Ever Sharp I have seen with Heath hallmarks; not even those earliest Ever Sharps with Heath’s patented clip bore these markings (Heath-made Ever Sharps are identified solely by Heath’s patented clip and distinctive metalwork).

The mark suggests that Heath supplied at least this cap and barrel to someone else, and the obvious buyer would be the Wahl Adding Machine Company . . . that possibility seems less obvious, however, upon closer examination of the pencil. Eversharps that sport John Wahl’s patented clip have a very clean, precise tombstone cutout into which these clips fit, as shown in Wahl’s patent drawings:

Douglas’ pencil has a more rough-cut opening to accept the clip, with gaps that are uncharacteristic for pencils made by Wahl; perhaps it was a retrofit, made by cutting out the area which would have been punched for a Heath patented clip:

One interesting possibility I considered is that Wahl’s patented clip might actually have been an innovation which originated in Heath’s facility rather than in Wahl’s. According to the patent application, John Wahl was actually the co-inventor of the clip, along with William H. Odlum, also of Chicago:

This was Odlum’s only writing instrument patent; much later, he patented several other innovations in machinery, but none were assigned to Wahl. Could Odlum have invented a version of Wahl’s clip earlier, while he was working for Heath? I found no evidence to support that theory, so that is just bare speculation.

One logical explanation is that Heath had leftover barrels after production of Ever Sharp pencils was transitioned to Wahl; that might also explain why the Ever Sharp imprint is double-stamped. Perhaps Heath re-stamped retrofitted barrels to add the company’s hallmark before offloading them to Wahl:

Although this explanation seems to be the simple answer, it has its problems. Why would Wahl, firmly established in manufacturing pencils by the time the Wahl-clip pencils were in production, have any interest in crudely retrofitted barrels stamped with Heath’s hallmark – especially plain barrels with none of Heath’s superior metalwork?

There’s one other possibility. In Charles Keeran’s 1928 letter to Wahl's directors, he accused Wahl of muscling him out of his ownership in the Eversharp Pencil Company; on the other hand, Wahl’s version of the story is that Wahl accepted Keeran’s stock in the company in lieu of payment for pencils sold on credit when it became apparent Keeran would be unable to pay for them. Wahl’s version is likely the accurate one.

There was probably a time, sometime in 1916, when Wahl declined to supply Keeran with any more Ever Sharps until some arrangement had been made to pay for the stock Wahl had already delivered to him. Perhaps Keeran scrambled to find another supplier, knocking once again on Heath’s door to see if the company would make his pencils.

The timeline for this possibility both fits and doesn’t fit. The patent for Wahl’s clip wasn’t filed until March, 1917 – long after Keeran had been divested of his shares in the Eversharp Pencil Company, which doesn’t fit.

However, when the patent application was filed is telling. By March, 1917, Keeran’s relationship with Wahl was strained, and within a couple months he would be ousted from Wahl entirely. During that tense time, Wahl might have filed the patent application for this clip months after it was developed, perhaps by Odlum and perhaps with Keeran’s input, after it was clear Keeran was on his way out.

If Odlum had developed this clip earlier, while Wahl was still supplying pencils for Keeran rather than making them on its own account in 1916, Keeran might have considered the innovation a “work for hire.” He might have felt entitled to take Odlum’s clip with him over to Heath, to see if they could make one like it, which Heath did – although somewhat crudely – repurposing leftover parts. After Wahl acquired Keeran’s stock in the Eversharp Pencil Company, Wahl would most certainly have put a stop to that.

All three of these possibilities are interesting. Maybe Heath actually developed what we now refer to as the “Wahl clip.” Maybe Heath dumped its leftover parts on Wahl. Maybe Charles Keeran re-engaged Heath briefly just before he lost a controlling interest in his Eversharp Pencil Company.

All of these theories are thin. However, any one of them might some day prove true, and any one of them would add an interesting footnote to the early history of the Ever Sharp.

No comments:

Post a Comment