This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 3; copies are available print on demand through Amazon here, and I offer an ebook version in pdf format at the Legendary Lead Company here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

There is a place, somewhere in the Universe, where all the bits and pieces of things come together and live in harmony . . . the ying of the barrel finds the yang of its long-lost cap; box and instructions finally return to the pencil you couldn’t figure out how to use. Rarely do we mere mortals see this place of Nirvana, as we paw endlessly through cigar boxes of junk at pen shows hoping to find the clip, the tip, the barrel for which we’ve been tirelessly and endlessly searching. Our tortured souls constantly yearn for the peace to be found in a place where all is made right.

It’s not all that bad, really . . . in fact, for most of us it’s the thrill of junk box archaeology that keeps our minds engaged in this stuff. If it was too easy, I know I’d be bored with it. This time, however, as the Universe pulled back the curtains and gave me just a glimpse into pencil Nirvana, all I could do was sigh contentedly and marvel at how nicely and perfectly this one came together.

All mysticism aside, this is pretty damned cool. A year or so ago I ran across an item in an online auction that I had to have:

Dur-O-Lite is kind of like the little brother of Autopoint. Acutally, it’s

exactly like the little brother of Autopoint: the company was formed in 1926 by former Autopoint executives who left Autopoint after the Bakelite Corporation acquired a controlling interest in the pencil company in 1925. Like Autopoint, Dur-O-Lite made removable-nose pencils which were only slightly different (the fact that there was mild disagreements, but no apparent legal scuffles over the invention illustrates how collaborative the design must have been); like Autopoint, Dur-O-Lite marketed their products primarily as advertising giveaways.

However, I think that everyone with a sense of humor must have left Autopoint for Dur-O-Lite. Autopoint, much as I like the company, remained stoic and serious . . .

“The Better Pencil” was the company’s slogan, best said with one’s head tilted backwards in Thurston Howell fashion, with one’s teeth gritted in a patrician and condescending sneer.

Over at Dur-O-Lite, however, they didn’t take themselves so seriously. If you get a chance, check out the trading cards Dur-O-Lite produced showing off its employees back in 1934, posted over at Bob Bolin’s site (

http://unllib.unl.edu/Bolin_resources/pencil_page/postals/Index.html). These guys had fun. Some days -- ok

most days -- I wish I worked there.

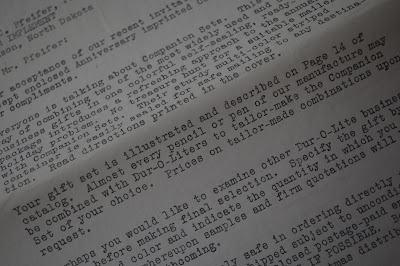

So you can imagine that when Dur-O-Lite reached its Thirtieth Annivesary in 1956, the company went all out to commemorate the event. The catalog is a hoot, and I promise one of these days I’ll scan and upload it to the PCA’s library. I would have been thrilled just to add the 1956 catalog to my collection, but this one came with even more: a personalized letter from the company:

and even the box in which it was mailed to the customer:

With a postmark of November 12, 1955:

At this point you might sigh contentedly. How perfect, you might think, that all these pieces stayed together after sixty years. You must be thinking this was the moment when I felt peace wash over me and I started chanting . . . oommmmmmmm. . ..

It was not. In fact, as happy as I was to find the catalog, box and letter together (by the way, there’s even a return envelope to Dur-O-Lite in the box), I couldn’t bear to write about this just yet. There was something missing from this, and the knowledge of

exactly what

wasn’t there was driving me frickin’ crazy.

“Accept enclosed Anniversary imprinted Companion Set with our compliments,” the letter begins.

“Your gift set is illustrated and described on Page 14 of catalog,” the letter continues. And sure enough, on page 14 . . .

Oh, how cool would that be!!! A boxed set with a pencil and lighter, imprinted with Dur-O-Lite’s Thirtieth Anniversary?

I like to think that there might be at least someone out there who empathize with the sweet but persistent agony this piece has caused me over the course of a year. All this wonderful information at my fingertips, tinged with the knowledge that things would have been even more . . . waaaaaay more perfecter if only the rest of it was there.

And just a couple weeks ago, as I trolled around through random online auctions just a couple weeks ago, it happened.

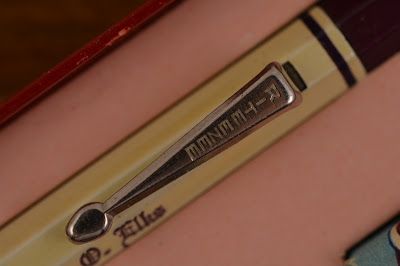

For what I considered a measly thirty bucks. Buy it now . . . I didn’t even have to bid.

Someone out there has no idea how happy they made me.

All is now right in my little corner of the Universe. Ommmmmmm....

Except for one thing . . . .

I wonder if that pencil was supposed to have a different cap?