This article has been included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 7, now available here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy the article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

Gary Weimer said it was his wife who spotted this while they were foraging around:

It’s another convertible like the ones shown in the article posted June 15. You can use it either within the case, or it can be removed from the sheath so you don’t need to unhook it from your watch chain:

Both of the elements which make this one unusual are on the top knob: “Spaulding & Co.” and “14kt.”:

Yeah, I had to pay gold value . . . but with a name I had not seen on a pencil before, what I really paid for was the story I would get to unravel. When I call Spaulding & Co. the “Tiffany of the Midwest,” the analogy is particularly fitting given the history of the firm.

Henry Abiram Spaulding was born in New York on November 11, 1837, according to americansilversmiths.org, which also reports that he was first employed by the New York jewelry firm of Ball, Black & Co. in 1857. He remained there until 1864 or 1865, according to different sources, when he went into partnership with Alfred L. Browne as Browne & Spaulding.

The 1864-1865 New York Directory lists Alfred L. Browne in “watches” at 565 Broadway, and I did not find a formal published partnership announcement in New York newspapers from 1863 through 1865 to establish exactly when this occurred. However, I did find an announcement – in The Chicago Tribune, not New York – on September 1, 1865, in which “Messrs. Browne & Spaulding, jewellers, who have recently opened at No. 570 Broadway” had exhibited a set of jewelry specially made for presentation to Ulysses S. Grant’s wife in recognition of his victory at Appomattox:

A trade card republished at americansilversmiths.org, which states that both Brown and Spaulding were “late with Black, Ball & Co.,” must date between 1865 and 1869, but the reference to their prior association suggests it would have been at the earlier end of this time period:

On August 3, 1869, The New York Times published a notice that John Howard Gray and George H. Brown had joined the firm, which was renamed Browne, Spaulding & Co.:

Several accounts, including a relatively contemporary biography of H.A. Spaulding in Industrial Chicago Vol. 4 (1894) state that Spaulding left Browne, Spaulding & Co. in 1871 to work for Tiffany & Co. Although this history is provided more than twenty years later, it was verified by notice of the dissolution of Browne, Spaulding & Co. on February 28, 1871, published in The New York Times on March 1, 1871; Browne was left behind to supervise the liquidation of the business:

There isn’t much documentation of Spaulding’s activities for the next sixteen years, although the biographical sketch in Industrial Chicago indicates that he was Tiffany’s general representative in Europe. When he returned stateside, however, it was not to New York: Spaulding went to Chicago, perhaps to explore a new opportunity – if not, then Spaulding was in the right place at the perfect time to do so.

Newell Matson was head of a prominent Chicago jewelry firm, N. Matson & Co. The partnership had been organized under that name in 1867 by Matson, Leverett J. Norton and William E. Higley, according to the partnership announcement published in The Chicago Tribune on January 20, 1867:

Tragedy struck four years later, when the Great Chicago Fire in October, 1871 obliterated more than three square miles of the city. Matson’s store and all of its inventory was utterly destroyed, but Newell Matson was a man of such character and conviction that he was determined to rebuild, declining offers to settle with his creditors for 50 or 60 percent of what he owed so that he could pay them every penny he owed to them. On the strength of Nathan Matson’s character, his creditors accepted payments, made accommodations and by 1885 the business had recovered to the point that it could be organized as a stock company, in large part so that Nathan Matson could slow down a bit.

Matson’s struggles had taken a toll on him, but through it all he was steadfast in his determination. “No man ever lived whose credit was better than N. Matson’s,” said one unidentified source in the Chicago Tribune on August 19, 1887. “He was universally regarded in the business world as the perfection of business honor and integrity. Without a dollar in the world he could have bought the earth.”

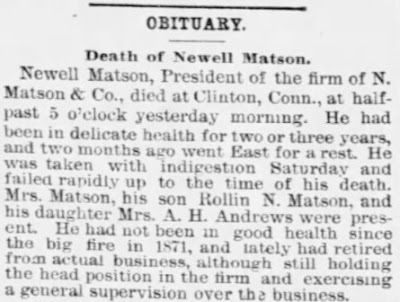

In May, 1887 Newell Matson went east to take a break from his management of the firm. In July, his health failed and he passed away at 5:30 a.m. on July 29, 1887 in Clinton, Connecticut:

Matson’s five heirs did not share his dedication, and since the assets of N. Matson & Co. were about equal to the company’s liabilities, they refused to put any effort or capital into the business. The Gorham Manufacturing Company, which had been accepting payments from Newell Matson on obligations that were as much as a decade old, was first of several creditors to secure judgment against the firm and secure the appointment of a receiver to oversee the orderly liquidation of the company, as reported in The Chicago Tribune on August 19, 1887:

On January 20, 1888, The Chicago Tribune reported that the receiver had nearly paid all of the judgment creditors in full; at that point, the judge ruled that the remainder of the company’s assets should also be administered by the receiver for the benefit of all of the firm’s creditors, including those who were owed money but had not yet been sued. Creditors were given until March 1 to present their claims for verification:

By May of 1888, the receiver’s job was finished, and the entire business was offered for sale, including all of its inventory, fixtures and the firm’s lease on the building. On May 12, 1888, the Chicago Inter Ocean published notice that sealed bids for the business would be accepted through May 17:

On May 18, 1888, the bids were opened and presented to Judge Gresham. The high bid was $35,000.00, but the judge ordered the receiver to extend the bidding until May 24, 1888:

On May 25, 1888, the Chicago Tribune reported that N. Matson & Co. was sold for $42,500.00 to W.R. Alling, 170 Broadway in New York, and James P. Snow, 3 Maiden Lane. The two were trustees for unnamed and unsecured creditors of the firm:

That same day, the Inter Ocean published an announcement that “Matson & Co.” had been “completely re-stocked with a larger assortment than is shown elsewhere in Chicago”:

Just a couple weeks later, The Chicago Tribune reported on June 5, 1888 that Judge Gresham had signed an order confirming the sale of N. Matson & Co. to “the creditors, who bought it in for $120,000.”

On October 15, 1888, The Inter Ocean reported that a stock company had been organized “to carry on N. Matson’s jewelry business.” The one-line remark was unclear whether this was restructuring or preparation for an acquisition:

The question was answered the following month. On November 29, 1888, The Inter Ocean published an announcement that the newly incorporated Spaulding & Co. had set up shop in the premises formerly occupied by N. Matson & Co. “Mr. Spaulding, for years of Messrs. Tiffany & Co.’s establishment, Paris, France, has reached this city,” the notice stated. “The future of this establishment should not be gauged by the present display . . . The old and inferior articles in the Matson stock have been sold to various tradespeople; nothing but goods of the highest standard will ever be shown in this establishment as now organized.”

Henry A. Spaulding organized the company along with several other businessmen, including Edward Forman – the receiver for N. Matson & Co. (according to Centennial History of Chicago, its Men and Institutions, published in 1905). Spaulding’s marketing plan was genius: using his French connections through Tiffany & Co., he imported luxury items from the Continent and set up a branch office for Spaulding & Co. in Paris, through which he coordinated accommodations and travel plans for those attending the Paris International Exhibition of 1889. Lavish receptions for those who wanted to see and be seen were held at the firm’s Chicago office, and the company quickly became a prominent fixture in downtown Chicago, on a par with Tiffany & Co.

It would be Henry Spaulding’s final triumph in a long career in the industry. He retired in 1894, having invested his amassed fortune heavily in the steel and copper industries – and lost it all in the Panic of 1893, an economic depression that lasted through 1897. Spaulding contracted pneumonia and died on February 9, 1904; a short obituary, hardly fitting of a man who had accomplished so much, appeared in the Chicago Tribune that day:

The obituary left out the tragic circumstances surrounding his death. On February 14, 1904, the Tribune reported that before Spaulding’s body had even been put in a coffin, fire broke out at his home – firefighters were barely able to save his body before the residence burned to the ground:

The firm Henry Spaulding founded, however, survived and thrived. I found two short bursts of advertisements which included pencils among the firm’s offerings, both published after Spaulding’s death. The earlier series, between 1907 and 1913, did not provide much detail concerning the type of pencils the firm offered, although one particularly elaborate advertisement, published in the Tribune on December 19, 1913, indicated that “Cigar and Cigarette cases, Match Boxes, Pocket Knives and Pencils may be had in the same pattern of engine turning.”

Spaulding & Co. emphasized writing instruments among its offerings again between 1921 and 1923. This advertisement was published in the Tribune on December 8, 1921:

Another advertisement, in the Tribune on December 9, 1923, included “gold pencils” among its “Gifts at $10 and less,” and gold fountain pens are included among those between $10 and $25:

Pencils such as the one shown at the beginning of this article are probably from the 1921-1923 era, and the insides were likely sourced from Cross (see https://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2021/06/rounding-up-victorians.html for others along these lines).

Spaulding & Co. remained in business as a prominent jeweler until 1989. While the store was closed with a sign in the window indicating the showroom was being remodeled, the Chicago Tribune reported on February 9, 1989 that Royal Copenhagen, the Danish-based porcelain and silver firm, would be opening a Chicago branch in Spaulding’s facilities. “A Spaulding official denied the retailer was going out of business, saying the firm would be involved in a ‘partnership’ with a firm, which he declined to identify,” the report stated.

On February 14, 1989, the Tribune followed up with a report that Georg Jensen, which had been acquired by Royal Copenhagen, was also moving into Spaulding’s quarters. “Where Spaulding fits in could not be determined,” the author wrote.

That would prove to be the last mention of Spaulding & Co., 101 years after Henry A. Spaulding founded the company from the ashes of N. Matson & Co. Spaulding’s fate was eerily similar to Matson’s – it simply ceased to exist, with its successor assuming nothing more than its location.

Thanks for posting this fascinating history of Spaulding, which I found by searching for "Spaulding & Co" to identify cross streets in Chicago in a black & white photo. The name appears on a building in the background.

ReplyDeleteDid Spaulding and Co. make snuff boxes?

ReplyDelete