This article has been included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 7, now available here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy the article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

One item in the mini-hoard of Victorian items that yielded last week’s Dederick combo attracted my attention and convinced me to bet heavy as I rolled the dice. Even in the fuzzy pictures online, I could see that it was unusual:

It’s that thing near the top, with what looks like a very early nib - a “spear” nib, as David Nishimura calls them. Since the seller had no idea it was a reversible pen and pencil unit, the seller shipped it exactly how it was shown in the auction pictures, with the nib hanging out there just begging for disaster.

Fortunately, it arrived safely, and while the case that houses the nib is unmarked, it is much larger than most of these are, more intricately engraved than most, and it is in perfect condition, too:

Here it is shown with its components disassembled:

I had not seen a nib like this one before, with intricate engraving like this but no maker’s imprint, so I emailed David Nishimura to see if he had any ideas who might have manufactured it. “I’ll bet it’s a ‘Eurkea’ nib made by E.S. Johnson,” he commented, noting that the imprint was probably on the part tucked inside the penholder.

Nishimura really knows his stuff. By the way, he already knew who Zachariah Dederick was, too. OK, so maybe this isn’t news . . . it’s just news to me.

However, this combo got me to thinking about Ephraim S. Johnson. This piece is from the 1850s, much earlier than the other Johnson things in my collection – most of what I have relates to his ubiquitous “Pearl” patent of December 5, 1871 (like that double-ended earspoon/toothpick from a few days ago). Come to think about it, that was about all I knew about the man, which meant it was time to learn a little more.

Two later accounts provide a little information about how and when Johnson got into the writing instruments business. One has been widely publicized: the February 5, 1919 issue of The Jewelers’ Circular -Weekly is a treasure trove of biographical sketches featuring many of the Victorian makers, and it included a short history of E.S. Johnson:

According to this account, Johnson’s firm was established in 1848, but this provides no other detail concerning Johnson’s early history (we’ll get to the later history in due course). However, another account published in 1877 provided the clues which unraveled the entire story:

This article, which ran in the Buffalo Daily Dispatch and Evening Post on September 13, 1877, purports to provide a general history of the early development of the gold pen (nib) industry in America, but as the article develops it becomes more of a thinly veiled touting of E.S. Johnson’s contributions, to the exclusion of all other nibmakers of the day.

The 1877 account traces the history of gold pens back to John Isaac Hawkins, who began embedding diamonds or rubies into the points of nibs in 1823. Hawkins, according to this account, sold his business to “Mr. [Orestes] Cleveland,” who hired Detroit watchmaker Levi Brown to make the pens for him. Brown relocated to New York in 1840, where he took on a young apprentice named Albert G. Bagley.

That is where our story picked up in an earlier article here: in “From Bagley to Todd,” tracing the succession of one firm’s history from Albert G. Bagley through what would become Edward Todd & Co., the earliest primary evidence I could find of Bagley’s entry into the pen business was in 1842, when he was adjudged bankrupt (the story begins in Volume 5, page 174).

At this point, the 1877 account branches off from the Bagley story: “Mr. Bagley had two partners by the name of Smith engaged with him in business interests, but from misunderstanding they dissolved their connection in 1847,” the report states. “The business was continued by the Smiths for some time on their own account in the same manner as it is now conducted by E.S. Johnson, of New York, who was an employe (sic) of the Smiths, and succeeded them in the manufacture of gold [pens], retaining many of the tools even now as mementoes of their former use.”

Bear in mind that this account was written thirty years later, but from what we know – including a lot of details I didn’t tell you before – E.S. Johnson’s early history can finally be revealed.

As mentioned in my previous article, the decision in a lawsuit Bagley brought against William Clarke (Bagley v. Clarke, 7 Bosw. 94) recited that Albert G. Bagley entered into an informal association with Gerrit Smith and Edgar M. Smith in May, 1846. A formal copartnership was entered into by the three on December 1, 1846 for a term ending in January, 1851, but the partnership was terminated early on August 10, 1848 due to Bagley’s “difficulties” with the Smiths.

At that point, the Smiths fade out of the Bagley story – but that is precisely when today’s story begins. Thirty years later, it was in E.S. Johnson’s best interests to trace his heritage back through Bagley to the earliest pioneers in the American pen industry – in 1848, however, it was in Johnson’s best interests to operate very discretely.

In early 1847, things were still going well between Bagley and the Smiths; on January 29, 1847 The Brooklyn Eagle threw its institutional support behind “its old acquaintance and school-boy friend, Mr. Edgar Smith (and a fine gentlemanly fellow he is!), encouraging readers to “Go to 189 Broadway!” “To procure one of Bagley’s beauties”:

However, shortly after this notice ran, Albert G. Bagley inexplicably disappeared – perhaps as a result of the scandal which erupted after he allegedly took in a 16-year-0ld girl who he impregnated. The Smiths alleged (as was revealed in later legal proceedings) that when Bagley left, he absconded with a large amount of gold kept at the firm’s offices.

On August 12, 1848, the Smiths published a notice of dissolution of the partnership in The New York Evening Post, indicating that they would continue business at “the old stand” at 189 Broadway, under the name of G. & E.M. Smith:

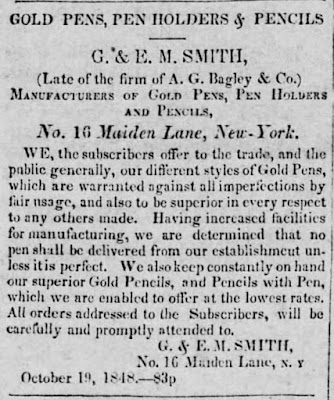

On February 15, 1849, an advertisement dated October 1848 appeared in The Perry County Democrat in Bloomfield, Pennyslvania, indicating that G. & E.M. Smith had relocated to 16 Maiden Lane:

Bagley had resurfaced, and apparently he was furious. As mentioned in my last article, he published warnings dated April 26, 1849, threatening prosecution against anyone copying his patented extending penholders:

Bagley also filed suit against the Smiths, alleging that he was owed damages for lost profits arising from the termination of the agreement, even though he returned to the business of making pens under his own name without so much as missing a beat. On April 27, 1849, The Evening Post reported that Bagley had won a verdict against his former partners:

Bagley had stepped back in and reclaimed the business location at 189 Broadway, together with the firm’s penmaking and nibmaking equipment, leaving the Smiths to procure pens from somewhere else – and they didn’t have go far. The 1849 New York City directory lists a gold pen manufacturer named Thomas H. Vanbrunt right around the corner, at 5 Dey Street, New York:

In the 1850 directory, Vanbrunt is shown at 177 Broadway, just a few doors down from “the old stand” of A.G. Bagley & Co. at 189 Broadway:

The Smiths remained at 16 Maiden Lane, but unlike Vanbrunt, neither is listed as a gold pen manufacturer. Edgar is listed with an occupation in “gold pens,” while Gerrit was making pencils:

The Smiths appealed the judgment rendered against them, and the case languished in the appellate courts for several years. On June 1, 1853, the Court’s decision was announced in Bagley v. Smith, 10 N.Y. 489: the case made legal history for the proposition that Bagley could sue for lost profits from his partnership with the Smiths, in addition to (and not offset by) the profits he was continuing to make by continuing the business in his own name. Judgment against the Smiths was affirmed, and that appears to be the end of G.& E.M. Smith; Edgar’s profession in the 1855 directory is listed as “real estate,” and Gerrit disappears entirely.

Thomas H. Vanbrunt, however, had disappeared from New York directories long before the appeal was decided. In fact, he disappears entirely until July 15, 1856, when a partnership dissolution notice appeared in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

E.S. Johnson’s notice comes out of the blue, and was likely published in New York only because Johnson’s gold pens were in circulation in New York City. Johnson never appeared in these directories during these early years, because neither he nor his business were located in New York – he was across the river in Jersey City, New Jersey.

When all of the pieces in this story are laid out in order, all becomes clear: Johnson claimed to have gone into business in 1848, just when A.G. Bagley’s partnership imploded. The 1877 account, influenced by Johnson, recites that he was employed by the Smiths – not by Bagley, which means whatever relationship he had with them arose after A.G.Bagley was dissolved.

That relationship with the Smiths was likely established when he was joined in New Jersey by Thomas Vanbrunt – outside of the jurisdiction of New York courts – to manufacture nibs for G. & E.M. Smith before the appeal was announced against the Smiths. Once the Smiths had left the pen industry, Vanbrunt apparently did, as well: at least as far as Ephraim S. Johnson was concerned.

After Johnson parted ways with Vanbrunt, Johnson apparently went on his own for a while; advertisements in 1862 and 1863 identify him only as “E.S. Johnson.” However, in the 1867 directory, there’s a separate listing for “E.S. Johnson & Co.,” and another penmaker is listed at 44 Nassau Street with him: Milo Newton Wells. The 1868 directory listing clarifies his middle name and adds that his residence is J.C. – that’s Jersey City:

Wells and Johnson are listed in association with each other through the 1874 directories, although in the last two editions, Wells’ address is listed simply as “Mo.” I wondered whether that might stand for Missouri, and I found evidence that was indeed the case: on October 3, 1874, The St. Louis Republican announced the names of those who had contributed items to a local raffle to benefit “the cotton premium.” One M.N. Wells was on hand to donate “3 gold pens, holders cases”

That must have proved to be an overly demanding commute. On January 29, 1873, Johnson and Wells jointly published a notice in The New York Daily Herald that they had mutually decided to terminate their partnership, effective January 2, 1873:

Johnson went alone again for awhile, before incorporating his business sometime before Trow’s copartnership directory was published for 1886, in which Ephraim is listed as president, while his son Ephraim Jr. is the company’s treasurer:

In the 1890 directory, a third character is added in the directory: Henry V. Terhune, who served as secretary and director:

In 1894, the directory specifies that both Ephraim and his son were simply “jewelers” in business at 26 Maiden Lane, and there is no mention of E.S. Johnson & Co. That address was occupied by W.E. White & Company, jewelers in the same directory, owned by Walter E. White who is also listed at that address.

According to the 1919 sketch in The Jewelers’ Circular, Ephraim Johnson “succeeded” his own company in 1897, and the business was carried on by his sons, Ephraim Jr. and D.T. Johnson (the latter of whom, according to this piece, was still running the company as of 1919). “Succeeded,” I believe, meant withdrew from: one later report indicated that “his head had troubled him, and he sometimes spoke gloomily of himself.”

On the evening of June 5, 1898, Ephraim Sherman Johnson retired to his room to read at his home in Yonkers, New York. The following morning, he was found dead, having apparently committed suicide by asphyxiation: he had turning on illuminating gas, and the tube was found next to him. The report in The Yonkers Statesman on June 6 indicated he left a widow, two sons and two daughters:

The drama didn’t end there. The company that issued Johnson’s life insurance policies in favor of his daughters was declared insolvent, resulting in years of litigation. One of his sons, Ephraim Jr., was adjudicated bankrupt in 1900 after starting another writing instruments firm with one of Leroy Fairchild’s sons, named Fairchild & Johnson.

Ephraim Jr., despite his financial issues, was the more successful in carrying on his father’s name. Although the 1919 Jewelers’ Circular profile indicated that Ephraim’s other son, D.W. Johnson, was continuing to operate E.S. Johnson & Co., it appears to have existed almost entirely in name only. The 1919 profile doesn’t identify the current location for the firm, but it is not listed in the 1920 New York City Directory. Perhaps E.S. Johnson & Co. had retreated back across the river to New Jersey; perhaps the 1919 profile was also the company’s obituary.

I have an original book from EA Johnson scrapbook from 1885

ReplyDelete