This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 5; copies are available print on demand through Amazon here, and I offer an ebook version in pdf format at the Legendary Lead Company here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

And second, he and I knew it had an Ohio connection:

C. – or maybe G – Sackersdorff is imprinted into the bone handle. We knew about the Ohio connection from my recently released book, American Writing Instrument Trademarks 1870-1953 (the book is available at https://www.legendaryleadcompany.com/store/p86/American_Writing_Instrument_Trademarks_1870-1953_.html):

Gustav Sackersdorff, “a subject of the Czar of Russia, residing and doing business at Cleveland, Ohio,” applied to register trademark number 28,675 on May 28, 1896, for “the facsimile of my autograph signature ‘Sackersdorff.’” In his application, he claimed to have used the mark since September 30, 1880.

The trademark was filed during that awkward time at the Patent and Trademark Office, during which drawings weren’t included in the registration cerficates – and for whatever reason, they weren’t preserved. Fortunately, the images can still be found from the Official Gazette, so I painstakingly went back through and tracked them all down, reproducing them all in the first section of the book. Here’s the image

The signature version of Sackersdorff’s trademark wasn’t carved into the humble bone pencil, for obvious reasons. The filing of the trademark, however, adds a dimension of understanding to this pencil – and its Ohio connections – which would otherwise have been forgotten.

In 1876, Gustav appeared in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, selling Russian lead pencils - almost assuredly wood-cased pencils, in the lingo of the day - and the local paper was proud to “pronounce them good.”

In 1882, the Wilkes-Barre Sunday News extolled the virtues of Sackersdorff’s Russian pencils, indicating that they were about a third the price as others on the market at the time. There’s a bit of inconsistency in the story though - the article claims the pencils are “pure plumbago,” which would be extremely soft, but states that the pencils could be stuck into wood without the point breaking. Note that the address provided for Sackersdorff was 63 4th Avenue, New York:

In Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania, they apparently didn’t see too many “real live” Russians, and Gustav’s appearance there, as reported in the July 21, 1882 Wyoming Democrat, seemed dubious as to whether he was the genuine article. “If his word is as good as his pencils we know he told the truth,” the article conceded.

By 1895, Wanamakers was advertising the “Perfect Lead Pencil” for 35 cents per dozen:

In fact, twelve years later, John Wanamaker still “said so.”

Gustav was married to an opera singer who, according to this account, sang with the Metropolitan Opera House. She died suddenly on January 5, 1908 at the Hotel Victoria in New York, and her death – reported on the front page of the Sun -- was ruled the result of apoplexy:

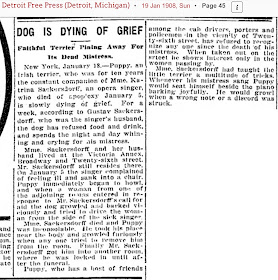

As noted in the article, Mrs. Sackersdorff’s faithful dog refused to leave her side and had to be forcibly removed. Days later, the terrier was reported to be refusing food and drink, dying of grief at the loss of its owner:

By the time Gustav was widowed, his fortunes had apparently changed, and he claimed he “had no friends in this country.” On August 24, 1908, the sixty-year-old Gustav – who was perhaps taking a cue from the house of Faber and going by the title “Count Augustus Sackersdorff” – checked into the Hotel Diana on West 35th Street. Half an hour later, he called the clerk to say he wasn’t feeling well and asked for a physician. Dr. Foote from the New York Hospital was summoned, but when he arrived shortly after, the Count was found dead.

Gustav’s death was also front page news, in the August 25, 1908 New York Tribune. While Dr. Foote believed the cause of death to be heart disease, the police suspected “unnatural causes,” citing reports from a friend of the Count that he did not expect to live much longer:

“Unnatural” does not appear to have meant “suspicious,” though. Another account of Gustav Sackersdorff’s passing, which appeared in the Benton Harbor (Michigan) News-Palladium the following day, shows Sackersdorff in an entirely different light: as a once-wealthy Russian Count, who once peddled pencils and was married to a famous opera singer, and who died penniless in a cheap New York hotel.

Fascinating story, with your usual level of research evident.

ReplyDeleteSehr interessante Story über den amerikanischen Zweig meiner deutsch-baltischen Familie!

ReplyDeleteH. Sackersdorff