This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 4; copies are available print on demand through Amazon here, and I offer an ebook version in pdf format at the Legendary Lead Company here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

LaFrance and the Good Dentist

Throughout David LaFrance’s years at the Boston Fountain Pen

Company, LaFrance was involved in the Agassiz Council Number 45 of the Royal

Arcanum, a local service organization.

On January 1, 1910, the Cambridge

Sentinel reported that LaFrance served on the banquet committee for an

event honoring the head of the club’s membership committee, and the

entertainment was furnished by the Agassiz Instrumental Quartet, in which a

prominent local dentist, Dr. William P. DeWitt, played the clarinet.

The DeWitt family became very close to LaFrance: in 1913, when LaFrance married, he and his

bride went on an “automobile party to the White mountains” with Dr. Newton A.

DeWitt (also a dentist in Cambridge), staying at DeWitt’s summer home for a

week before returning to their new home at 5 Day Street, just a few doors down

from DeWitt’s house at 19 Day.

In the latter half of 1918, The DeWitt-LaFrance Company was quietly organized in Cambridge, Massachusetts to manufacture writing instruments. William P. DeWitt and David J. LaFrance filed a patent application for a new lever-filled fountain pen, with a spring-loaded single bar, on May 10, 1918 (the patent was issued on April 15, 1919 as number 1,300,849). However, not even the local press reported anything about the new company until 1920, when the Cambridge Tribune noted on October 16, 1920, that the company had been organized approximately two years earlier and had been making its new pencils “for a few months.” “About two years” fits nicely into a timeline which assumes that David J. LaFrance was in Sheaffer’s employ until Sheaffer’s patent was all but secured. “A few months,” however, is an understatement – unless, as I believe, the article suggests that DeWitt-LaFrance was making its new pencils for only a few months, but was making some other pencils before then.

DeWitt-LaFrance pencils are relatively easy to date, because the distinctive clips were patented separately from the pencils on which they were mounted. Side clip models are stamped either "Patd." or "Pat Pend." on the clip, a reference to patent 1,350,412, which was applied for on September 13, 1918 and was granted on August 24, 1920. In addition, the pencils barrels are separately marked with either “Pat.” or “Pat. Pend.” DeWitt and LaFrance applied for two separate patents for the pencil mechanisms themselves on October 2, 1919, which were granted on July 25, 1922 as patent 1,423,603 and on November 22, 1922 as patent 1,434,684.

|

| Figure 8: Pencils manufactured by The DeWitt-LaFrance Company, including a few marked “Signet” and sold through Rexall Stores. |

|

| Figure 9: From top, “Pat. Pend.” on clip and barrel; “Patd.” on clip and “Pat. Pend.” on barrel; “Patd.” on clip and “Pat.” on barrel. |

One of DeWitt-LaFrance’s first customers, we know from the DeWitt-LaFrance patent history, was the Samuel Ward Manufacturing Company, a Boston stationer. Beginning at the turn of the last century, Ward traded stationery products under its house-brand name, SAWACO. When Samuel Ward first offered mechanical pencils as one of its product lines, though, it did so under the name “Redypoint.” The choice of the name was unfortunate, because Brown and Bigelow had already started marketing pencils under the name “Redipoint.” It appears Ward was quickly forced to abandon the name, reverting to the use of its established SAWACO name on its house-brand pencils, as well.

|

| Figure 10: Typical (but rare) DeWitt-LaFrance pencils marked “Redypoint” and “SAWACO.” |

|

| Figure 11: Detail of imprints on Redypoint and SAWACO pencils. All known examples of both varieties are marked “Pat. Pend.” on both the clips and the barrels. |

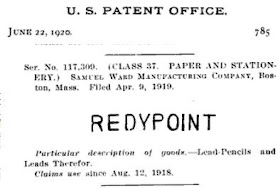

However, in Samuel Ward’s trademark registration for the

name “Redypoint” in connection with pencils, Ward first claimed to use the name

on August 12, 1918: that is two months before Sheaffer’s patent application was

granted, right around the same time DeWitt-LaFrance was established, and before

DeWitt and LaFrance filed their patent applications for their distinctive clip

and pencil.

|

| Figure 12: Redypoint trademark filed by The Samuel Ward Manufacturing Co. |

Before that answer is presented, though, it is important to identify the characteristics of the earliest Sharp Point pencils, as they were originally introduced in July, 1917. Surviving examples of the first Sharp Points are extremely rare, and it is only by comparing those earliest examples to a recent discovery that David J. LaFrance can be conclusively identified as the inventor of the pencil.

Development and Refinement of the Sharp Point

The earliest Sheaffer Sharp Points – the ones made before Kugel

established a factory to make them at 440 Canal Street In New York – are easy

to distinguish from later models in three respects: first, they have a crown-style top

reminiscent of the Eversharp. Second,

the font used for the imprints is the same Winchester-inspired, spiky lettering

found on contemporary Ever Sharp pencils.

Third, the clips had a straight mounting where the clip was soldered to

the barrel.

|

| Figure 14: Detail of imprint on earliest Sheaffer Sharp Points. Note the same font as used on contemporaneous Eversharps. |

Soon after the pencils were introduced, “wings” were added

to the lower portion of the mounting, so that the upper part of the clip

resembles a bowler hat – collectors refer to these as “bowler clips.” On April 10, 1919 (just as the 440 Canal

Street factory was opening), Walter Sheaffer filed an application for a design

patent for a pencil, showing the “bowler clip” as well as a flared, bell-shaped

cap. Although design patents only

protect the outward appearance of an object, the wings were doubtless added for

stability rather than aesthetics.

Sheaffer later applied for and received a utility patent for the

distinctive flared, bell-shaped cap, under the pretense that it would be less

prone to denting (a claim which any Sheaffer pencil collector will tell you is

pure hogwash). Finally, Sheaffer

abandoned the “bowler clip” for the familiar ball clip the company used well

into the 1920s.

|

| Figure 16: Sheaffer’s Utility Patent number 1,554,604 for the bell cap, filed in May, 1919. |

|

| Figure 17: Sheaffer’s patent 1,531,419 for the company’s familiar ball clip. |

In the final installment tomorrow, it all comes together . . . part five is at http://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2016/12/wahl-sheaffer-and-race-for-boston-part_30.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment