This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 4; copies are available print on demand through Amazon here, and I offer an ebook version in pdf format at the Legendary Lead Company here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

Note: this is the second installment in a five-part series. Part one begins at http://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2016/12/wahl-sheaffer-and-race-for-boston-part.html.

The Chicken Rancher’s Next Move

On New Years’ Day, 1916, less than two weeks after Colonel

Smith was lounging alongside his poultry without a care in the world,

The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer

announced that Smith was emerging from his short retirement to sell pens for

The Boston Fountain Pen Company in fourteen states, with his headquarters in

Chicago.

[i]

Charles Keeran comments in his 1928 letter that the Chicago

department store “Marshall Field & Co. also featured this [Boston Fountain]

pen above all others,” so Smith’s sudden association with a distant company is

not as random as it might initially appear; it is also possible, if in fact

Smith expressed dissatisfaction with Sheaffer to Keeran at their dinner on

September 17, that Keeran suggested that Smith look into selling Boston

Fountain Pens as an alternative. If Keeran had anything more to do with Smith’s

association with Boston, he would have taken credit for doing so; he didn’t, so

it is likely that the recently unemployed and resourceful Smith developed his

relationship with The Boston Fountain Pen Company on his own.

[ii]

|

| Figure 13. This advertisement in the September 20, 1916 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune establishes that Marshall Field & Co. was carrying both Boston Fountain pens and Ever Sharp pencils . . . alongside Waterman Ideals. |

No record has surfaced to date of where Smith’s Chicago

offices were located, but he must have spent some time at Keeran’s offices in

the Lytton Building: just a week after

the initial announcement that Smith was handling the “Boston Safety Pen

Company,”

The American Stationer announced

that Smith added a pencil to his Boston pens: Keeran’s Ever Sharp

[iii] The account states that Smith’s contract to

sell Eversharp pencils was with “Keeran & Co.” in the states of Ohio,

Indiana, Michigan and Kentucky. Keeran &

Co. was the separate company Keeran formed to distribute Ever Sharps

manufactured by his “Eversharp Pencil Company.”

While Keeran indicates in his 1928 letter that at some point around this

time – by mid-1916 -- Wahl’s officers had purchased a majority of the shares in

the Eversharp Pencil Company, Keeran remained in control of his distribution

company.

The state of Illinois is conspicuously absent from Colonel

Smith’s Ever Sharp territory (whether this is because Keeran had lost control

of that state by virtue of Wahl’s control of Eversharp, or because Keeran

wanted to keep it for himself). However,

in four states, William Smith’s sole writing instrument lines were Boston

Fountain Pens and Ever Sharp pencils. Whether

Smith offered the pair together in one box or not, it was Smith – and neither

Wahl nor Sheaffer – who thought that a fountain pen and mechanical pencil would

“fit in very nicely” together and made it happen.

Smith, the former Waterman man, Sheaffer man and chicken

rancher, was masterfully orchestrating his next marketing stunt. With trade announcements in The American Stationer still hot off the

press, he was poised to take the Midwest by storm. In just a couple weeks’ time, all of the

major players in the Midwestern stationer’s industry would be gathered together

in one room, ripe for Smith to make a big impression and even bigger sales, at the

black-tie event around which the industry’s year revolved, and in which Smith

reveled: the 1916 Chicago Stationers’ Dinner.

Black Ties and Red Faces: The

Unreceptive Corner at the Stationers’ Dinner

As mentioned earlier, William Smith was an annual fixture at

the Chicago Stationer’s Dinner, held in January each year. “It was an occasion that brought forth all

that goes to make up good fellowship of the right kind,”

The American Stationer reported in 1914. “It was a moment when men, away from their

business cares for a short time—gathered for their annual festivities—listened

to words that had in them the ring of truth and the elements of weight.”

[iv] Smith had attended for many years; in 1914,

he had missed it due to his falling out with Waterman; in 1915, he returned

triumphantly on Walter Sheaffer’s arm. The

fourteenth annual banquet, to be held on January 15, 1916, would be

different: for the first time, “the

ladies were invited.”

[v]

Smith capitalized on the event: after the introductions and a chorus of

“America,” the menus were presented, and each of the ladies found on their

plate a Boston Fountain Pen in sterling, engraved with their name and

accompanied by Colonel Smith’s card.

[vi]

The Colonel’s publicity stunt was a significant breach of

etiquette, on an evening during which the men were supposed to be “away from

their business cares”: while The American Stationer’s annual reports

were very detailed year after year with respect to who was present and with

whom they were associated at the time, there had never been an occasion such as

this when an attendee used the event to promote their individual products – and

there is no indication that Smith similarly promoted Waterman’s or Sheaffer’s

pens in previous years.

The “officer” and a gentleman Smith doubtless left the wives

in attendance swooning, and the fact that Smith escaped rebuke for his stunt is

a testament to his status in the Chicago stationer’s community. Not everyone would have been Even though – all perhaps, except for one. “W.A. Sheaffer, of the W.A. Sheaffer Pen

Company, came on from Fort Madison, Ia.,” the account reports, “and was busy

doing his share of the entertaining during the evening.” Fred Seymour from Waterman was also on hand,

“kept very busy shaking hands during the course of the evening.”

[vii]

The recently jilted Walter A. Sheaffer must have been

blindsided by Colonel Smith’s “clever stunt,” and it is difficult to imagine how

a Boston Fountain Pen inscribed with Mrs. Sheaffer’s name would have survived

the evening. It is, however, easy to

imagine what Sheaffer’s “share of the entertaining” must have been as he

watched his former Chicago manager steal the show that evening, perhaps

commiserating with Fred Seymour, the Waterman executive who had just a couple

years earlier been dispatched to Chicago to escort the wayward Colonel Smith

back to Waterman’s Chicago office.

|

| Figure 14. Walter Sheaffer shakes hands – and likely his head – while Col. Bill Smith steals the show. |

Smith might as well have thrown his drink in Walter Sheaffer’s

face. Sheaffer was still in the midst of

a bad breakup with former business partner George Kraker, and for the second

time, he was watching a close and important business associate abandon him and

turn competitor. In the case of Kraker, Sheaffer retaliated

with protracted patent litigation over the rights to the lever-fill pen design

both were using. Smith, however, would

be a different matter – all he was doing was selling someone else’s pens. If Sheaffer wanted to shut Smith down, his next

logical move would be to acquire Boston.

If the

deeply personal conflict between Walter Sheaffer and William Smith were not

enough for Sheaffer to think about attacking the Boston Fountain Pen Company,

the events which unfolded in the first half of 1916 guaranteed that

Sheaffer would do so.

The Race for Boston Is On

The gregarious Colonel Smith was a pied piper of pen

salesman, and as his Boston Pen/Eversharp pencil business gathered steam, other

prominent salesmen from Chicago stationers’ houses soon found themselves within

his gravitational pull. On January 26,

1916,

The American Stationer reported

the resignation of Eddie Dick, the fountain pen and “clasp pencil” department

head of Stevens, Maloney & Co. “It

is whispered that Eddie will assist one of the well-known salesman in the

fountain pen business in this territory,” the article reported.

[viii]

Smith’s success also appeared to lured William H. Newhall

away from Shea Smith & Co., although reports are somewhat conflicted as to

whether Newhall’s relationships with either Shea Smith or Colonel Smith were

exclusive. In April, 1916, both

Geyer’s Stationer and

The American Stationer reported that

Newhall and Smith had formed a new company, the Newhall-Smith Company.

Geyer’s

reported that Newhall-Smith’s offices were on the seventh floor of the

Harris Trust Building at the corner of Monroe and LaSalle; while the company

had a “good-sized” display room for their samples (which were expanded to

include Solidhead Tacks, Featherweight Eyeshades and Gordon Brown’s china

markers, called the “Perfect Paper Pencils”), the company’s presence in the

upper floors of an office building suggests that Newhall-Smith’s business model

was supplying stationers rather than competing with them.

[ix] Eddie Dick, of course, turns up shortly

thereafter “assisting” Newhall-Smith.

[x]

As for Charles Keeran, Newhall-Smith’s success in promoting

his pencils was equal parts blessing and curse.

The increased demand fueled by Newhall-Smith caused Keeran to pressure

Wahl to increase production and build up inventory, but in the process Keeran

overextended himself. According to a

1921 account by C.A. Frary, “the owner of The Eversharp Pencil Company found

himself at the end of his resources. He

could not pay his bills. We, as a result

of being his manufacturers, were the chief creditors. Consequently, it seemed that the ‘easiest way

to get the money due was to take over the nearly-defunct company.”

[xi] Some of Wahl’s directors had acquired a

controlling interest in Eversharp, and Keeran’s offices were relocated to the

Peoples Gas Building in Chicago.

The Boston Fountain Pen Company was prospering from its

relationship with Colonel Smith, in more ways than one. Not only was Boston enjoying increased sales

in the Midwest, but Boston had the best intelligence available as to what

Walter Sheaffer’s plans would be. Smith

would certainly have understood that while only one man would be left standing

as between Kraker and Sheaffer, the basic idea of a lever-filled fountain pen

would not only survive, but would be fair game.

As Waterman was demonstrating with the introduction of its PSF line of

lever fillers in 1915, anyone could produce a lever filler, as long as the

pitfalls of those improvements peculiar to the Sheaffer, Kraker and Craig patents

were avoided.

[xii]

The extent to which Smith influenced the Boston Fountain Pen

Company’s direction is unknown, but if

Smith had some insight into Walter Sheaffer’s plans and if Smith left Sheaffer because he thought the lever filler was a

smashing idea upon which he would be better off capitalizing with another

company, then what happened next makes perfect sense:

The Boston Fountain Pen Company developed its own version of

a lever-filler.

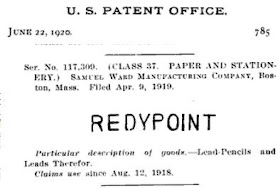

The patent application for Boston’s version was filed on May

1, 1916 by David J. LaFrance, who had been Boston’s superintendent since 1905. LaFrance’s version neatly avoided all of the arguments

in the Sheaffer litigation over how to attach a compression plate to the barrel

of the pen in the most elegant way: it

wasn’t attached at all. Rather, Boston’s

compression plate hung by a spring from the lever itself, so that lifting the

lever stretched the spring and deflated the sac; when the lever was released,

it would snap shut and be held flush with the barrel by the tension of the

spring.

|

| Figure 15. David J. LaFrance’s patent number 1,209,978 for a lever-filling fountain pen, applied for on May 1, 1916. Note the date the patent was issued: December 26, 1916. |

Boston and Colonel Smith wasted no time rushing the new pen into

production and to market. On July 8,

1916,

The American Stationer reported

that Newhall and Smith had returned from a trip to Boston, and a week later

reported that W.H. Newhall claimed that Eddie Dick owed him a new pair of pants

due to Dick’s “zeal” in demonstrating how a Boston Safety is filled. Meanwhile, Colonel Smith had embarked on a

three-week long sales trip, long even by Smith’s standards, in which he would

visit such far-reaching places as “St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, Des Moines,

St. Paul and Minneapolis.”

[xiii]

|

| Figure 16. Boston lever-filling fountain pens, from the collection of Roger Wooten. |

Whether or not William Smith had anything to do with

Boston’s development of a lever-filled fountain pen, the fact that Boston did

so, and when they did so, worked out perfectly for Smith. At the end of 1915, Smith was branch office

manager for a company making pens that were selling like wildfire . . . but which

may or may not survive, depending on the outcome of pending litigation. By July of 1916, he’s free of Sheaffer, doing

the same job selling fountain pens that worked like and looked like a Sheaffer,

with none of Sheaffer’s baggage inside – and with a companion pencil, to boot.

It was at that precise time, just as everything was taking

off for Newhall-Smith and the Boston Fountain Pen Company, a little birdie told

Charles Keeran the Boston Fountain Pen Company might be for sale. Colonel Birdie, we’ll call him.

The Pieces of the Puzzle Come Together

Once the Boston Fountain Pen Company’s new pens emerged as a

litigation-free alternative to Sheaffer’s enormously popular lever filler,

Boston was in the same predicament in which Keeran had found his Eversharp

Pencil Company the previous year – the company itself became a valuable

commodity practically overnight. Although

Charles Keeran’s 1928 account of the events which followed does not contain many

of the dates, working his timeline backwards it appears that the wrangling

began in mid-1916.

[xiv]

The chain reaction which resulted in the sale of the Boston

Fountain Pen Company is speculative, but the preceding well-documented story

suggests it likely began with overtures, threats or a combination of the two

from Sheaffer. All of the other

characters were satisfied with the status quo:

Smith was happy selling the pens, not making them, and neither Keeran

nor Wahl would have had any motivation to disrupt what was becoming a very

profitable enterprise.

Walter Sheaffer, on the other hand, had strong personal

reasons for attacking the company, if not from the moment Smith resigned, then

certainly the morning after that fateful Chicago Stationers’ Dinner in January. Smith’s success distributing of Boston

Fountain Pens and Ever Sharp pencils in early 1916 would have added a business

motivation to any desire Sheaffer might have had to settle a personal

score. Add to these factors Boston’s

introduction of a competing lever-filled fountain pen, and acquiring Boston

would become a necessity if Sheaffer was to preserve his domination of the

lever-filled pen market.

Smith had always landed on his feet before, but he had

reasons to be very concerned about a possible Sheaffer buyout of Boston. He had burned bridges with both Waterman and

Sheaffer, investing himself and likely his resources heavily in his new Smith-Newhall

enterprise. Smith would have known to a

certainty that if a sale of Boston to Sheaffer went through, he would be back

on his chicken ranch in ten minutes flat.

William E. Newhall likewise had a lot riding on Smith’s fate. News reports at the time are somewhat

ambiguous as to whether Newhall had entered into the Newhall-Smith partnership

in addition to or instead of his association with the established Shea Smith

& Co., but the fact that Newhall-Smith was wholesaling pens, pencils and

other products to other stationers suggests that Newhall’s ability to actively

represent Shea Smith’s interests was severely compromised. If all of Smith’s eggs were in one basket

(pun intended), it wouldn’t be an enviable basket for Newhall to share if

Walter Sheaffer came in to clean house – especially given Sheaffer’s history of

suing even those who were only tangentially involved in an alleged infraction.

Since both Smith and Newhall had an interest in keeping

their existing product lines intact, it isn’t surprising that one or both of

them would try to find a friendlier buyer for Boston. Wahl, whose directors now controlled Keeran’s

Eversharp Pencil Company, would have been the obvious choice. If Wahl directors owned both The Boston

Fountain Pen Company as well as the Eversharp Pencil Company, Smith and Newhall

would be assured they would keep Boston Fountain Pens paired with Keeran’s Ever

Sharp pencils.

Keeran reports that C.S. Roberts, Wahl’s vice president and

the man he attempted to persuade to buying Boston, was hesitant -- with good

reason. The Eversharp Pencil Company’s

relationship with Newhall-Smith was not an exclusive one, and Ever Sharp

pencils were selling briskly with or without the Boston Safety Pens,

particularly on the west coast. In

addition, Boston’s newfound success was a double-edged sword: while Wahl’s executives found it relatively

easy and cheap to acquire Keeran’s startup company, the Boston Fountain Pen

Company was an established business, and their slick new lever filler would

doubtless make Boston on the one hand profitable yet on the other, more expensive

to acquire.

Besides, Roberts might legitimately have thought, although Sheaffer

might want to buy Boston, whether to settle a score or for whatever other

reason, in July, 1916, he might have assumed Sheaffer wasn’t in any position to

do so. The Courts had yet to determine

the outcome in Sheaffer’s patent litigation, and if Sheaffer lost, there likely

would be no Sheaffer Pen Company and business would continue as usual. Wait and see, Roberts might legitimately have

thought.

Roberts, Keeran, Smith and Newhall didn’t have to wait long. On August 23, 1916, the United States Patent

Office determined the “priority” of Sheaffer and Craig’s respective patents, determining

that it was Sheaffer, and not Craig, who invented Sheaffer’s “double bar” lever

filler. This was not the end of the Sheaffer-Kraker-Craig

litigation, which was running on two parallel tracks: the case in which Walter Sheaffer had been

testifying throughout 1915 was the infringement litigation, filed as the

parties continued to scuffle in the Patent Office over whose invention came

first. The patent office decision in the

interference case didn’t end the infringement litigation, but it did preordain

one of the outcomes: since each of the

parties was suing the other for infringement, the Patent Office decision meant

that Sheaffer could not have infringed on Craig, but Craig must have infringed

on Sheaffer. All that was left for the

court to do in the Sheaffer litigation was decide the remedy for what was now

found to be the wrong.

|

| Figure 17. The patent dispute between Sheaffer and Craig was not finally decided until 1918, but the Patent Office decision announced in August, 1916 made Sheaffer’s ultimate victory inevitable. |

The patent office decision in the Sheaffer case added

urgency to the pleas of Smith, Newhall and Keeran for a friendlier buyer, now

that Sheaffer would clearly survive and would have the capital to pursue Boston

with greater ferocity. According to

Keeran’s letter, this is when C.S. Roberts finally agreed to send Keeran to

Boston “to look into the matter.”

The decision likely would have softened Charles Brandt to

the idea of selling, too. Even though

Boston’s patent appeared to stand on very solid footing, Sheaffer’s success in

patent litigation stood in stark contrast to Boston’s bad luck, beginning when

Brandt founded the company in 1905 and Brandt’s petition for a trademark for

“Boston Fountain Pen Company” was denied solely because the mark spelled out

the word “Company” but his petition was signed with the word Company abbreviated

as “Co.”

[xv] Just two years before Sheaffer’s 1916 victory,

The Boston Fountain Pen Co. lost an infringement action it filed over pens made

by the Sanford & Bennett Co.; to add insult to injury, the story in

The American Stationer reporting the

outcome of the litigation on April 18, 1914 appeared on the same pages as a

sizeable advertisement for Sanford & Bennett’s allegedly infringing pens.

[xvi] Any threat of litigation from Sheaffer, no

matter how hollow, would have been cause for concern to Brandt.

According to Keeran, he traveled to Boston one afternoon in

September, 1916, met Charles Brandt for the first time at 4:00 p.m., and “in

one hour bought the whole works for $50,000.00.” Working backwards from Keeran’s timeline, when

his second sixty-day option period expired on January 10, 1917, this meeting would

have occurred around September 12, 1916.

[xvii]

No other documents have been found to substantiate Keeran’s

account, and it seems highly unlikely that Keeran met Brandt for the first time

and negotiated the purchase of his entire established business in an hour. When Keeran arrived in Boston in early

September 1916, he would have needed some introduction if he was to have any

credibility. He had one. On September 16, 1916,

The American Stationer reported that “W.H. Newhall, of the

Newhall-Smith Company, made a trip to Boston last week on business.”

[xviii]

The price Keeran says he negotiated, $50,000.00, is the

equivalent of more than $1.1 million in 2015.

Keeran didn’t have that sort of cash, and since he was no longer in

control of his Eversharp Pencil Company, he couldn’t speak for the company,

either: all he could do was negotiate an

option for sixty days at whatever price Brandt would accept and take it back to

the decision makers back in Chicago.

Wahl’s management did not give his deal the warm reception Keeran

anticipated, and as the sixty-day option was running out, Wahl “was not yet

ready” to exercise the option. With the

option set to expire around November 10, 1916, Keeran reports that he traveled

to New York (and not Boston), where Charles Brandt met him and, “after a long

conference in his attorney’s office,” Keeran was able to persuade him to extend

the option for another sixty days.

Neither Keeran nor any other source indicates who Charles

Brandt’s attorney in New York was, but a good guess is an 1891 graduate of

Columbia, who had offices at 99 Nassau Street and 319 West 87

th

Streets: Charles Brandt, Jr.

[xix] The elder Brandt’s reluctance to extend Keeran’s

option may have been nothing more than his desire for a professional opinion or

a family meeting with Charles Brandt, his son George (who managed the works),

and Charles Jr., the attorney; after all, his initial option to sell “the whole

works” was negotiated in the span of an hour, when Keeran and Newhall had shown

up unannounced. However, Brandt’s

hesitation may also have been because Brandt sensed he may be able to get a

better deal – and the evidence suggests that pressure from Sheaffer had likely been

building since Keeran first paid Mr. Brandt a visit.

The Kugel Maneuver

In mid-September, at almost exactly the same time Keeran

reports that he negotiated the initial option to purchase the Boston Fountain

Pen Company, Sheaffer’s New York office manager, B.T. Coulson, abruptly

resigns.

The American Stationer and

Office

Appliances both attributed Coulson’s resignation to nothing more than “ill

health and a much-needed rest” and indicated that “[h]e will still retain his

interest in the company as well as his official connections.”

[xx]

It is likely true that Coulson’s health was

deteriorating: pneumonia eventually claimed

his life in February, 1920.

[xxi] However, the report in

Geyer’s Stationer indicates there may have been more to the story,

announcing that while Coulson would retain his official title of Vice

President, he “in fact severed his active association with the company.”

[xxii] Was Coulson quietly relieved of duty because

he failed to consummate some sort of a deal with the Boston Fountain Pen Company? The evidence suggests that he was.

Concurrently with the announcements of Coulson’s retirement

was the announcement that upon Coulson’s departure from New York on October 1,

he would be replaced by “an old fountain pen man,” The Parker Pen Company’s

former Chicago office manager, Arthur L. Kugel (misspelled as “Kudel” in the

Geyer’s account).

[xxiii] Kugel, who was being brought into New York

from Chicago to replace an office manager forced to resign ostensibly due to

his health, would obviously attend first to the most pressing matters affecting

Sheaffer’s New York office.

Thanks to

the

The American Stationer, we know

what that most pressing matter was. According to a news

report published in the October 7, 1916 edition, Kugel spent his first week as

Sheaffer’s New York representative . . . in Boston.

[xxiv]

A Different Sort of Nor’easter

It took some talking in November, 1916, but Keeran says he

was able to persuade Brandt to extend his option for an additional sixty days,

ending on January 10, 1917. Keeran is silent, however, on what happened in

between the time he negotiated this extension and December 26, 1916, when he

and C.S. Roberts boarded a train for

Boston to exercise the option. The deal

was apparently all but done in the minds of Newhall and Smith, who disbanded

their company: the last reference to Newhall-Smith

is in connection with Newhall’s trip to Boston in September, 1916, and a month

later,

The American Stationer

reported that Smith attended the convention of the National Association of

Stationers and Manufacturers in Atlanta – no longer on behalf of the company

which bore his name, but representing The Eversharp Pencil Company.

[xxv]

As for Newhall, he returned to his

former position at Shea Smith & Co., and a 1922 biographical sketch in

Office Appliances makes no reference to

his former involvement with Smith. If

Newhall burned any bridges when he left Shea Smith, all was quickly forgiven

and forgotten.

[xxvi]

It is possible that Wahl’s directors dispatched C.S. Roberts

and Keeran to Boston on the day after Christmas to exercise the option for

accounting reasons, hoping to close out the transaction and spend the cash

before the end of the fiscal year.

However, there is a more attractive theory for the sudden urgency: on

December 26, 1916, the Boston Fountain Pen Company became significantly more

valuable.

On that very day, the United States Patent Office awarded

David J. LaFrance his patent for Boston’s version of a lever-filled fountain

pen.

Walter Sheaffer and his boots on the ground, Arthur Kugel, would

have known the same thing. If someone

else had patent rights to make a pen which, for all practical purposes, looked

just like the ones Sheaffer was making, would the public necessarily care what

was inside, so long as it worked? In

Sheaffer’s fight with Kraker, there could be only one winner: with that struggle all but won in late 1916,

Sheaffer was now facing another, more difficult challenge. He had to find a way to maintain his near monopoly

on lever-filling pens, this time against a competitor whose design didn’t

violate his patent rights.

At that crucial moment, Sheaffer caught a break when C.S.

Roberts pulled a stunt which nearly killed the deal for Wahl. According to Keeran, Roberts believed that

Keeran had agreed to overpay for Boston, so Roberts did not bring the

agreed-upon $50,000.00; instead, he only brought a check for $25,000.00, hoping

to talk Brandt down by half when they arrived.

That’s half a million, in today’s dollars.

Roberts’ timing could not have been worse, because Brandt

was not in a bargaining mood. According

to Keeran, “the owner not only wouldn’t take twenty-five, but he wouldn’t take

fifty thousand.” And why should he? Brandt’s stock had increased dramatically in

value when the patent was awarded (the modern equivalent would be a tick up in

value for a pharmaceutical company on the day a patent is awarded to it), and Sheaffer

was probably nipping at Brandt’s heels, with either a competing offer, legal

threats, or a combination of the two.

Keeran says that after he and Roberts consulted with an

attorney, they were advised that if they wanted to force the sale, they needed

to tender the full agreed price; Roberts, who by this time realized his

miscalculation, hastily contacted Chicago and had the remainder of the money wired. Keeran and Roberts then went back to Brandt,

who refused a certified check for

$50,000.00. Remember, that would be more than a million dollars today.

So, according to Keeran, he and Roberts settled into a

nearby hotel for two weeks to play rummy, while “the lawyers” worked things

out. During this time, Keeran says, “Mr. Brandt offered me $20,000.00 if I’d

let him off.” In 2015 dollars, that’s

nearly half a million! There is only one

explanation for this: Walter Sheaffer was

offering Brandt a lot more money, probably in excess of $70,000.00.

Brandt and his lawyers finally relented, and when the

transaction closed, Keeran reports, “[Roberts] was really enthused for the

first time.” Roberts, the same man who so

reluctantly brought a check for $25,000.00 to Boston on December 26 was

“enthused” two weeks later to spend twice that amount? Of

course he was. Sheaffer was prepared to

pay much more, and Roberts was now convinced he had gotten a deal.

No direct evidence has yet surfaced establishing what was

negotiated during those two weeks of rummy games. However, as any lawyer who has been in the

trenches for any length of time will tell you, there is rarely a clear, black

or white, win or lose. Charles Brandt

did not simply see the light, thumb his nose at Walter Sheaffer, agree that

selling his company pursuant to his agreement with Charles Keeran was the right

thing to do, convince Sheaffer to go quietly into the night, close the deal and

have everyone live happily ever after.

What everyone involved got in January, 1917 was something less than what

they wanted. Among attorneys, there’s a

well-known saying: the perfect

settlement is one with which no one is happy.

The surviving physical evidence clearly points to what the

terms of that settlement were.

The Compromise, Part One: as to Fountain Pens

For many years, collectors have noted that the earliest Wahl

pens have Sheaffer levers rather than Boston’s lever system. A century later, one of the theories for this

apparent anomality is that the Boston lever wasn’t as effective as the Sheaffer

“double bar,” but that opinion is based on the performance of Boston’s levers a

century later than when they were made.

At the time they were made, Boston’s springed compression bars may well

have had significantly greater “spring,” and may have been every bit Sheaffer’s

equal in effectiveness.

|

| Figure 18. Identical pens, one stamped with a Boston Safety Fountain Pen imprint, the other with a Wahl Tempoint imprint. From the collection of Roger Wooten |

However, all of the evidence of the gathering storm which

surrounded Boston’s purchase suggests that one of the terms of Walter

Sheaffer’s surrender of the Boston Fountain Pen Company to Wahl was to saddle

Boston with an obligation to use Sheaffer’s levers on all of its lever filled

pens before the company was sold, subject to this obligation, to Wahl.

|

| Figure 19. The levers of both pens shown in Figure 18, when lifted, each have a patent date of November 24, 1914 stamped on the side – a reference to Walter Sheaffer’s patent number 1,118,240. From the collection of Roger Wooten. |

Cliff Harrington, in the spring, 2001 issue of

The Pennant, revealed the details of a 1918

Wahl catalog he discovered, which had been annotated by C.W. Thornton, Wahl’s

cost accountant, with detailed production costs for the pens. Among these costs, Thornton indicated, was a

five cent per lever license fee. “It was

not clear whether this was paid to Sheaffer or to some other rights holder,”

Harrington stated,

[xxvii]

but when all the events described in this article are put together, there can

be no doubt now.

|

| Figure 20. Walter Sheaffer’s patent date was also stamped on some early Wahl pens with the familiar Wahl lever. From the collection of Roger Wooten. |

[i] The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer, January

1, 1916, at page 30.

[ii]

While Keeran states that he had seen and admired Boston Safety Pens being sold

at Wanamaker’s New York in 1913, it is noteworthy that Keeran – who was

extolling his contributions to Wahl – did not take credit for giving Smith the

idea to sell the Boston Fountain Pen.

[iii] The American Stationer, January 8, 1916,

at page 32.

[iv] The American Stationer, January 17,

1914, at page 3.

[v] Geyer’s Stationer, January 20, 1916, at

page 10.

[vi] The American Stationer, January 22,

1916, at page 41.

[viii]

The American Stationer, January 26,

1916, at page 26.

[ix] Geyer’s Stationer, April 20, 1916, at

page 11.

[x] The American Stationer, April 22, 1916,

at page 36.

[xi]

Frary, C.A., “What We Have Learned from Marketing Eversharp,”

Printers’ Ink, August 11, 1921, at page

3. Frary indicates that the buyout

occurred by virtue of an exchange of stock after the end of the holiday season

in 1916, but the acquisition must have occurred earlier in 1916; an increase in

production in anticipation of Newhall-Smith’s sales is the only likely cause.

[xii]

Barnes’ 1903 patent for a lever filler of a different design assured that

Sheaffer would never acquire a monopoly on the basic concept of a pen with a

rubber sac deflated with the use of a lever.

[xiii]

The American Stationer, July 15,

1916, at page 32.

[xiv]Keeran

reports that his renewal of his option to purchase the company, for another 60

days, ended on “about” January 10, 1917; therefore, his original option would

have expired around November 10, 1916 and he would have negotiated his deal

with Charles Brandt around September 10, 1916; prior to that, he says he tried

to persuade Wahl “for months” after hearing from Bill Smith that the company

was available.

[xv] Ex Parte Boston Fountain Pen Co., Official

Gazette of the United States Patent Office, June 27, 1905, at page 2531.

[xvi] The American Stationer, April 18, 1914,

at page 34.

[xviii]

The American Stationer, September 16,

1916, at page 8.

[xix] The Catalogue of Officers and Graduates of

Columbia University (1916), at page 616.

[xx] The American Stationer, September 16,

1916, at page 25 and

Office Appliances,

October, 1916 at page 164.

[xxi] Office Appliances, April, 1920, at page

61.

[xxii]

Geyer’s Stationer, September 14,

1916, at page 12.

[xxiv]

The American Stationer, October 7,

1916, at page 18.

[xxv] The American Stationer, October 21,

1916, at page 112.

[xxvi]

Office Appliances, September, 1922,

at page 24.

[xxvii]

Harrington, Clifford M., “Early Wahl Production Costs.”

The

Pennant, Spring, 2001, at page 29.