This article has been edited and included in The Leadhead's Pencil Blog Volume 5; copies are available print on demand through Amazon here, and I offer an ebook version in pdf format at the Legendary Lead Company here.

If you don't want the book but you enjoy this article, please consider supporting the Blog project here.

(Note: this is the second installment in a series of articles, the first of which begins at http://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2017/05/the-brothers-woodward.html).

Once I had pieced together the history of Woodwards & Hale, later Woodward & Brothers in hand, something nagged at me a little bit. Here’s David Nishimura’s picture of the examples in his collection:

After the first installment of this article ran, David added this comment:

Some further notes on the Woodwards in the photo, from top to bottom:

1. WOODWARDS & HALE imprint, gold brocade "FORGET ME NOT" barrel, GF crown, pale yellow faceted stone

2. WOODWARDS PATENT imprint, center section turns to extend nozzle, pale violet faceted stone

3. WOODWARDS & HALE imprint, silver brocade "FORGET ME NOT" barrel, dark purple faceted stone

4. WOODWARDS imprint, perpetual calendar, simple silver seal end

5. WOODWARDS & HALE imprint, perpetual calendar missing top ring, silver waffle seal end

6. WOODWARDS & HALE imprint, perpetual calendar, onion finial

7. WOODWARDS & HALE imprint, perpetual calendar, simple silver seal end

David’s description as to that second one from the top is particularly illuminating, because it makes sense of Thomas Woodward’s patent number 1,625 issued on June 10, 1840:

David doesn’t have an example of Woodward’s second patent, number 1,823 issued on October 14, 1840 – but that was more or less just a tab to keep parts from unscrewing themselves and from the looks of things, it might not have worked very well, anyway. Still, one would be nice to find!

Now we get to the part that nags at me. Both of Woodward’s patents were issued in 1840, after the dissolution of Woodwards & Hale in 1839 . . . but Woodwards & Hale was making pencils as early as 1833 (and, if the composition date of the ad is correct, as early as June, 1832):

So whose pencil was Woodwards & Hale making in the early 1830s?

The convention of identifying products as patented in those early days was different than in later decades, when an actual patent date or number would be stamped on an item. Before the 1850s, an innovation would be marked, as is the case with David’s example, with “Woodward’s Patent.” We’ve seen that with other earlier pieces as well, such as those marked “Lownd’s Patent” and “Addison’s Patent.”

If you were licensing someone else’s patent, however, you wouldn’t particularly want their name stamped on your product. For example, if Woodward & Brothers were making pencils using Thomas Addison’s design, stamping “Addison’s Patent” on the side would only advertise for a competitior!

But Addison’s patent wasn’t issued until 1838; six years earlier, Woodwards & Hale was making pencils like the other ones shown in David’s picture, as well as my example:

Whose design was this? The list of likely suspects is a very short one. In

American Writing Instrument Patents 1799-1910 (shameless plug), I include a section in which all known patents are organized by date, and only 27 patents for any type of writing instrument were issued in the United States prior to 1840: of those, only 8 were for pencils:

Joseph Saxton’s patent of April 11, 1829;

William Jackson’s patent of July 27, 1829;

John Hague’s patent of August 16, 1833;

James Bogardus’ patent of September 17, 1833;

Elwood Meeds’ patent of June 26, 1835;

Jacob Lownds’ patent number 32 of September 22, 1836;

Thomas Addison’s patent number 736 of May 10, 1838;

John Hague’s patent number 1,291 of August 16, 1839; and

George Simon’s patent number 1,364 of October 12, 1839 (assigned to Stockton).

Of these eight, we can rule out the last four - I’ve written about the Lownds patent and this isn’t it (

http://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2016/10/about-time.html), and the same goes for Hague’s patent of 1839 (Joe Nemecek’s example was featured in

http://leadheadpencils.blogspot.com/2016/01/sleeping-at-switch.html). The Addison patent is for a screw drive advance, not a slider, so that isn’t right either, and Joe Nemecek has an example of the Simon (Stockton) patent, which was a little different and was issued too late in the game to represent the pencil Woodwards & Hale made nearly a decade earlier.

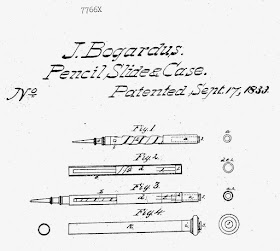

The last five patents are tougher to compare, since the patent office fire of December 15, 1836 destroyed all record of four of them. The only one that survived was the Bogardus patent, and even though it is specifically titled “Pencil Slide & Case,” it shows a mechanism advanced by a worm drive, not a simple slider:

That leaves Saxton, Jackson, Hague and Meeds. Three of the four of these – all but Hague – were issued in Philadelphia. In the early Nineteenth Century, would a Philadelphia patented pencil be manufactured in New York? Maybe, but I think it unlikely, since the industry was much more localized at the time.

So let’s take a closer look at Hague’s 1833 patent. I’ve never seen an example, and the only evidence I’ve found that they were ever made was a “hard times” token bearing a date of 1837:

On the reverse are the words "S. Maycock & Co. / 35 City Hall Place N.Y. / Everpointed Pencil Case Manufacturers Saml. Maycock John Hague." This is to my knowledge the only evidence of a Hague pencil possibly being made pursuant to Hague’s earlier 1833 patent – maybe they were unmarked sliders (which would defy convention, since you’d expect them to be marked “Hague’s Patent”); maybe Maycock was making something different or unpatented, with Hague riding along as a partner. However, what these tokens suggest is that while Hague was an inventor, he was not a man with the manufacturing capability to turn out the product: for production, he was dependent upon others.

Samuel Maycock shows up in Longworth’s 1836-37 New York City directory, as a “pencilm.” at the address shown on the advertising tokens: 35 City Hall Place:

So where was Maycock in 1832 and 1833, when Woodwards & Hale were making pencils such as those David and I have found?

He isn’t listed. His first appearance in Longworth’s is in the 1834-1835 directory.

And where was John Hague in 1832-1833? He was a general silversmith, located at 177 Greenwich:

The Longworth’s directory for 1833-1834 is interesting. John Hague remains listed as a silversmith, but he’s moved to 662 Water Street:

Meanwhile, there’s a listing for a “Thomas & Hague,” pencil case makers, at that same address:

If it was Hague’s pencil, why wasn’t it “Hague & Thomas?” Perhaps for the same reason suggested by Hague and Maycock – that Hague was dependent on partners to see his pencil into production?

Hague’s association with Augustus Thomas was brief. Notice of the dissolution of their association appeared in the

New York Evening Post on May 24, 1834:

The 1834-1835 directory continues to list John Hague as a silversmith at 662 Water Street, but Augustus Thomas had moved: he’s listed as a “silverpencil mak.” at an unspecified location on Cherry Street, with his home address listed as “Attorney”:

It isn’t until the 1835 directory that we find John Hague identifying himself as being a pencil maker, at the 35 City Hall Park address shared with Samuel Maycock:

In the 1838-1839 directory, S. Maycock & Co. remains listed as a pencil manufacturer, but the firm’s location had moved to 221 Pearl Street:

Hague, however, remained at 35 City Hall Park:

By 1842, Hague had relocated to 12 Dutch:

It was at this location that history records another event suggesting that John Hague’s business sense was not as refined as one would expect after more than a decade in the business. On January 15, 1844, the

New York Evening Post reported that two men conspired to persuade Hague to accept a promissory note for pencils Hague sold in the amount of $150.00, from a signer who turned out to be a “man of straw.”

The two men were later convicted, with one receiving a lighter jail term due to his advanced age.

It is perhaps unfair to make assumptions about a person based on a fragmentary record of events transpiring more than a century and a half earlier. However, the picture of John Hague that emerges from this little evidence suggests that Hague was a general silversmith without either the manufacturing capability or the business sense to make pencils on his own; twice he was involved in short-lived partnerships to manufacture pencils, and in neither of them was he the headliner, even though it was he who patented a pencil design. Even after more than a decade in the trade, he was duped by a simple confidence scam.

It’s possible that simple slider mechanisms such as my example and most of David’s were never patented by anyone in the United States, but were merely American copies of Mordan and Riddle’s 1822 patent in England. However, if Woodwards & Hale get their start making pencils which were patented here, John Hague’s 1833 patent is the strongest possibility. Hague was likely to be persuaded to license his design; Hague apparently lacked the ability in 1832 to manufacture his pencils in quantity; and Woodwards & Hale would have been unlikely to stamp Hague’s name on their pencils - particularly after Hague became involved with Thomas & Hague, S. Maycock & Co. and then identified himself as an independent pencil maker.

It’s conjecture, but a lot of the conjecture I throw out there eventually pans out. Whether evidence which surfaces later confirms or refutes my theory, that the simple slider pencil was patented in the U.S. by John Hague in 1833, it’s a win either way since the truth always seems to work its way to the surface.